International Women’s Day: Equality and Work in the Screen Industry Under the Microscope

By Dr Sheree Gregory

Bob Dylan said it best in his song 'The Times They Are a-Changin'. Well, aren't they? In 2016 there is a lot to celebrate on International Women's Day. According to conventional wisdom, the past half-century or so has seen unprecedented change. Sociologists and other writers have not been able to resist the temptation to endlessly celebrate and diagnose the idea that ours is a time of unrelenting radical change. More visible today is a public voice calling out gender inequality, sexism, and violence against women. Recent debates about gender targets and quotas in politics and the screen industry are further examples. There are questions, problems and solutions posed to deconstruct the seemingly natural and normal social order that undermines our values of equality, diversity and inclusion.

Indeed, one of the critical challenges for policy makers and employers in the paid workforce is equality and diversity management.

In reflecting on the media coverage of the lack of diversity represented among nominees at the 88th Oscars ceremony last week, I wonder why the screen industry is not equipped to deal with diversity. So what's happening?

Above: Kate Winslet in The Dressmaker.

Above: Kate Winslet in The Dressmaker.

The television coverage of the Oscars Red Carpet primarily shows women paraded in front of the camera lens dressed-up as a visible reminder of gender inequality. Not one female is among the best director (in feature film) nominees. There has only ever been one female director awarded the Oscar in that category in the history of the awards.

According to Screen Australia, 'Of the top 250 films from any country at the Australian box office in 2014, only 8 per cent were directed by women'.i

The 2016 Oscars not only reinforced the power of the 'male gaze'; the screen stories are more likely to be told through the eyes of a male character and director of Anglo descent.

The disparity in gender and cultural diversity is integral to the picture of success and achievement at the Oscars. This picture tells us that the industry is about exclusion; it is narrow and limiting in its view of audiences and collective experiences and understandings.

The world being shown at the Oscars on screen is a type of illusion of reality that serves to reinforce an older, dominant set of norms and beliefs. Like good lighting technique and direction, the audience's attention is being directed to a particular vision. This manipulation drives storytelling and invites a belief in what is on screen. After all, the human eye is attracted to the brightest object in the frame.

The politics of gender and diversity behind-the-lens, the under-representation of female directors and lack of cultural diversity is a real problem that has been largely absent from policy.

'Studies of inequality or discrimination at work show that the approach of "diversity management" or "managing diversity" has been well documented since the 1990s, and that this approach was welcomed by those seeking to transform organisations in the direction of greater equality, fairness, inclusion and justice.'ii

'Diversity relates to gender, age, cultural background, disability, religious belief, pregnancy, and family responsibilities. It refers to the many ways in which people are different and similar, such as educational and socioeconomic background, geographic location, marital status, and more.'iii Our society is diverse and should transfer to the workplace, organisational culture and businesses across industries.

Indeed, diverse organisations and businesses that harness diversity are powerful. It is well documentediv that businesses which create and manage a diverse workforce are successful and sustainable. Perhaps power relations are one key dimension ─ a dominant group is resistant to surrendering and sharing some of their power.

We need to explore solutions to the resistance to gender equality and cultural diversity in the screen industry to equip workforces to deal with diversity. These measures include cultural intelligencev, society-wide approaches to equality and diversity, and acknowledgement that work goes on backstage in our households.

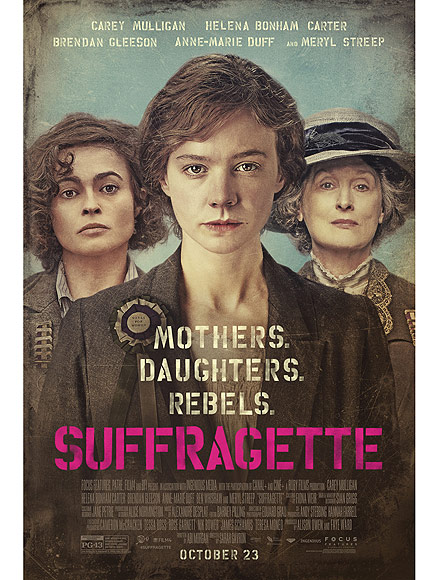

Above: Suffragette movie poster.

Are we looking in the wrong place?

The unequal gender distribution of labour within the screen industry mirrors society-wide trends: women are less visible in leadership roles in paid work, and men are less visible in the participation in caring labour. The caring demands that happen in the home are largely contested and invisible, yet these issues remain some of the most vexed in social and public health.

We need to look deeper into what these issues say about us as a society. The issue does not lie in 'fixing up' individual women film directors, even though common perception may read it that way (which is principally the issue).

Policy development, cultural intelligence, diversity management, and society-wide approaches

Screen Australia has recently released its Gender Matters: Women in the Australian Screen Industry reportvi and plans over three years to implement initiatives to address gender inequality in the Australian screen industry. These initiatives include changes to funding programs and distribution, assessment criteria and infrastructure to increase the participation of women. This is a significant step forward.

There remains much work to be done. On this International Women's Day, let's not forget that flexible workplace arrangements, the national Paid Parental Leave, the Dad and Partner Pay schemes, and Screen Australia's gender equity policy, are enacted in a context where women still perform more unpaid work. As sociologist Arlie Hochschild observes, to look only at changes in the system of paid work is to look at only 'half the problem'. We need a society-wide approach to gender equality and cultural diversity that includes shining a light on our values, assumptions, norms and practices that also take place in the home and community life. Until then, inequalities will likely re-emerge in new forms – as well as remain in conspicuous places like the Oscars.

Dr Sheree Gregory

Dr Gregory is a recipient of a 2016 Women's Fellowship at Western Sydney University, for which she is researching gender equity, policy and practice in the screen industry. She is Lecturer in School of Business, and Member of the Institute for Culture and Society

Email: s.gregory@westernsydney.edu.au

i Gender Matters: women in the Australian Screen Industry report (opens in a new window), November 2015, p. 4.

ii David knights Vedran Omanovi 2016, '(Mis)managing diversity: exploring the dangers of diversity management orthodoxy', Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, vol. 35, no. 1, p. 5.

iii R. J. Stone 2013, Managing Human Resources, Wiley, Milton, Chapter 14: 'Managing diversity', p. 599, 4th edition. See also: Natalie Burg, 'Businesses harness the power of diversity for growth', Forbes (Online), 24 December 2013.

iv R. J. Stone 2013, Managing Human Resources, Wiley, Milton, Chapter 14: 'Managing diversity', p. 599, 4th edition. See also: Natalie Burg, 'Businesses harness the power of diversity for growth', Forbes (Online), 24 December 2013.

v Ien Ang 2011, 'Navigating complexity: from cultural critique to cultural intelligence', Continuum, vol. 25, no. 6, pp. 779-794.

vi Gender Matters: women in the Australian Screen Industry report (opens in a new window), November 2015, p. 4.

Posted: 6 March 2016.