Sports, Sexism and the Law: Some Contextual History

There is abundant evidence that sexism is common, if not endemic, within sport. It can be found to different degrees in the sex- and gender-based stratification of organisational power, remuneration and media representation. In the face of this evidence, sport's apologists tend to mount a defence on two fronts – first, sport may be sexist in some respects, but so is wider society. Why, it is asked, should sport be singled out for special criticism when 'society is to blame'? The second, even more reactionary justification is that sexual inequality in sport is the natural order, because it is marked out as a social space where men have an inherent genetic advantage. Sport's ruthless, performance-based meritocracy, then, results in male dominance not, it is claimed, because of entrenched, calculated sexism, but because of the inexorable iron laws of 'nature'.

These alibis are routinely produced during the periodic scandals that erupt within sport. While they do not go unchallenged, they have proven resilient because of the specific history of sport as a social institution. I will briefly trace that history, because it reveals why it is particularly difficult to counter sexism within sport.

Every time an Olympics comes around, references to the Ancient Games suggest that sport is a practice that stretches back to antiquity. But this is a misleading narrative – the Ancient Olympics and other athletic festivals in Ancient Greece bore very little resemblance to the Games revived by the French aristocrat Baron Pierre de Coubertin in 1896. The Modern Olympics are a pastiche of recovered elements of the Ancient Games, British private school sport and market town recreational events in the English countryside (most famously the Wenlock Olympian Games). The Western origins of these developments should not be discounted – organised, competitive, commercialised sport is one of the West's most successful 'gifts' of cultural imperialism to the world, an effective form of 'soft power' operating long before the term was coined.

Today, the term 'Prolympics' is a more accurate descriptor of the post-amateur, government- and corporation-sponsored Games. But one element that has remained fairly constant as folk games morphed into professional sport is male domination. Women were not allowed to compete in the Ancient Olympics and de Coubertin tried to keep them out of his revived version, declaring that the Olympic spirit required:

the solemn and periodic exaltation of male athleticism, based on internationalism, by means of fairness, in an athletic setting, with the applause of women as the reward.

Ironically, women have a stronger place in the 21st century Olympics than in most other domains of sport, although it took the organisation of their own successful Women's Olympics in the 1920s along the way. But the sport-patriarchy nexus still weighs heavily on their prospects in sport. In considering the role that law might play in accelerating or retarding women's sporting advancement, there needs to be due acknowledgement of the impact of sport's lore on potential legal remedies.

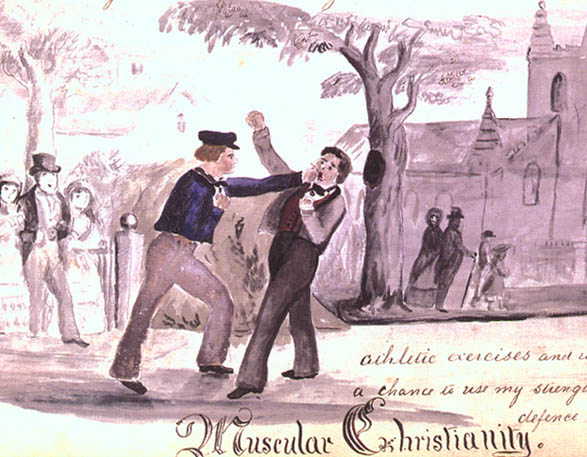

Sport is historically a male-dominated sphere of popular culture, and during the late-19th century it came to define masculinity itself. There are several reasons for this connection between sport and approved modes of being male. Anxieties (shared by de Coubertin after France's capitulation in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870) about urban men becoming soft and losing their capacity to wage war engendered moves to encourage them to 'get physical' in a competitive environment. Because of the belief that the 'child is father to the man', this meant that competitive athleticism (sometimes represented as Muscular Christianity) should be instilled in boys. As compulsory schooling was becoming established, it was no longer necessary to rely on parents to cajole their indolent sons to embrace competitive physical culture.

Above: [The Christian belief is] "that a man's body is given him to be trained and brought into subjection, then used for the protection of the weak and the advancement of all righteous causes," writes Thomas Hughes, author of the much-loved novel 'Tom Brown's School Days' in support of Muscular Christianity.

Compulsory sport had much to offer boys in the passage to becoming men. It offered legitimised violence in societies subject to the 'civilizing process' wherein citizens were being encouraged to settle disputes through negotiation and legal process rather than with fists and weapons. It signalled hope of transferrable skills from the sports field to the battlefield, including taking orders from the (usually socially superior) 'captain', cooperating as a team, and using trained physical skills and dispositions to win contests that produced winners and losers. The easy adaptation of sports metaphors of winning contests and defeating rivals also helped to obscure the brute realities of body counts and military destruction, while enhancing sport's prestige by associating it with glorious feats of war. Elements of these skills could also be transported to discipline workers whose lives of labour were now dictated by the exigencies of industrial time rather than the seasonal rhythms of agriculture.

Considerable resources from both government and civil society were invested in building up sport as a masculinist social institution. When in the 20th century sport was transformed into both a major industry and a pivotal element of broadcast media, it became even harder for women to make serious inroads into the male bastion of sport. A male sport star (and, later, celebrity) system emerged out of this 'sportsbiz', largely leaving the old ethic of amateurism – which abhorred pay for play – behind. But sport also retained much of its heroic Olympian mythology as a magical space that transcended everyday life and struggle, which included harking back to the idea of the Olympic truce involving the cessation of conflict and the free passage of athletes through war zones during the Ancient Games.

A further irony here is that sport became a key means of expressing nationalist sentiment that sometimes exhibited xenophobic and chauvinistic characteristics. Sportsmen came to match military warriors as symbols of national identity. Those engaged in team contact sport in particular were celebrated as ideal representatives of neighbourhoods, cities, regions and countries. The media, both private and public, made them into household names, providing the single most important source of revenue for elite sport, supported by all three tiers of government in the name of healthy citizenship and national pride. While society in general was proclaimed to be the beneficiary of sport conceived as a gender-neutral social good, it was men who received most of its kudos and material reward. Contemporary sport's combination of corporate capitalism and state subsidy has created an institution that has reinforced male power behind a veneer of common sense market logic and equal opportunity rhetoric.

This does not mean that women have been consistently excluded from involvement in sport or entirely subjugated within it. There is an established history of female sport achievement, and sportswomen and teams have been lauded and, in a small minority of cases, especially in individual sports, achieved something like parity with men. But they have struggled against the automatic allocation of predominantly supporting organisational roles, while sportswomen have generally received inequitable recognition, media attention and remuneration.

The sport market has been largely designed around the idea that sport is, in the first instance, male territory, supported by a vast media apparatus in which mostly male sport journalists cover male athletes in male-dominated sports. Systematic sexual segregation in sport, which is officially intended to ensure equality and prevent men from dominating women's sport, has largely functioned to produce a vertical hierarchy in the name of a horizontal one. In cultural terms, this problem is exacerbated by the consistent association of sport with manliness(opens in a new window). While men – including those who do not fit the mould – approach sport as a confirmation of orthodox gender identity, the reverse is the case for women, who have to address residual notions that sporting excellence and application is somehow at odds with femininity.

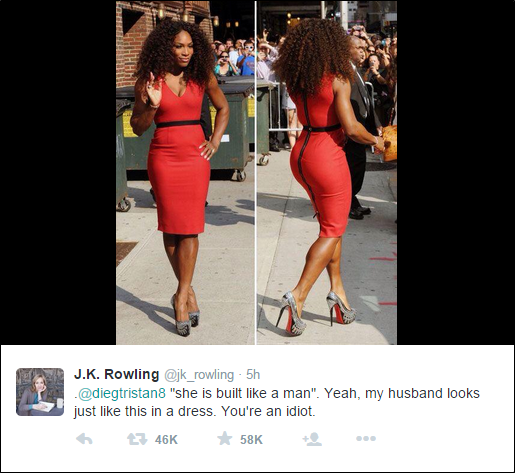

Above: 'Harry Potter' author J.K.Rowling tweeted a message to commemorate Serena Williams' victory at the 2015 Wimbledon tennis championships. Shortly after, Twitter user @diegtristan8 responded that the "Main reason for [Williams'] success is that she is built like a man". Rowlings response, which highlights how sportswomen have to continually 'prove' their heterosexual femininity, went viral.

It is for this reason that sportswomen frequently have to accentuate the conventional appearance of heterosexual femininity in order to provide reassurance that they are still 'real' women. Indeed, women are rewarded for cultivating an overtly sexualised image with greater media attention and sponsorship. Even if they do not cooperate in this regard, the commercial media are likely to sexualise them anyway, as well as to disparage the appearance of sportswomen whose bodies they regard as unattractive and/or overly masculine and implicitly lesbian.

Whereas sportswomen have to 'prove' their heterosexual femininity in the face of accusations that it masculinises them, for men sport is still used as a weapon to police the boundaries of approved masculinity, in particular punishing and repressing homosexuality, which is stigmatised as an expression of feminised weakness. It is for this reason that hardly any elite professional sportsmen in the peak of their careers have come out as gay or bisexual (opens in a new window). The world of sport still exhibits a strong preference for an outmoded sex and gender order that unconsciously and reflexively places straight men at its apex, women at is base, and is profoundly unsettled by the very notion of the intersexual and the transgendered.

Above: Olympic swimmer Ian Thorpe announces he is gay in a 2014 interview with Michael Parkinson. The swimmer said he was "ashamed" he had lacked the courage to "come out" sooner but had feared the reaction: "I didn't know if Australia wanted its champion to be gay," he said.

This is a rather bleak picture that has been painted to counter the tendency for sport aficionados (among which I count myself) to romanticise the object of their passion and to obscure its manifest deficiencies. There has been progress towards gender equity in sport, but it is both slow and patchy. If one of society's most prized institutions is not radically reformed, the negative social consequences are profound, not least because in countries like Australia sport is widely held to be definitive of nationhood. Sport cannot remain a citadel of sexism while battles are waged on all other fronts from the home to the workplace to the political sphere.

The law, it can be suggested, might operate as an 'accelerant' of progress in sport. This was certainly the case in the US with the introduction in 1972 of Title IX(opens in a new window), which declared that:

No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.

Anti-discrimination law can be effective in countering some of the more blatant manifestations of sexism in sport, as well as the attachment of strings to public funding as occurred, for example, in February 2016 when:

Federal Sports Minister Sussan Ley and Australian Sports Commission (ASC) chairman John Wylie [wrote] to the 30 top funded organisations setting out their expectations for change(opens in a new window).

"In 2016, we can think of no defensible reason why male and female athletes should travel in different classes or stay in different standard accommodation when attending major international sporting events …

The ASC is now proposing to make gender-neutral travel policies for senior major championships a condition of investment by the ASC in a sport".

But there are limitations to the use of law and regulation in the interest of sport and equity. For example, the (Australian) state of Victoria's Equal Opportunity Act 2010 covers:

playing, coaching, umpiring, refereeing and administering sporting activities.

'Sporting activities' under the Act includes a wide range of activities and is not limited to competitive field sports. It also includes activities that may be thought of as recreational rather than purely sporting, and can include games where physical athleticism is not a factor. For example, a sporting activity can include things like chess and debating.

But there are also many general and specific exceptions in the Act that, although individually defensible, provide opportunities to circumvent the intention of the legislation in key areas such as resourcing.

The law is an important component of the anti-sexism armoury but, as has been argued here, in sport it must confront deeply entrenched institutional values and practices that tend to reproduce sexual inequality as natural and normal. A particular tactic that must be countered is the routine appeal to the unfettered operation of the 'mediasport' market. Sport and broadcast media are not commercial markets that have emerged fully formed out of thin air. Both have received major public subsidies and access to public assets, including publicly owned space and spectrum. Men's sport has reached its current pre-eminence only after two centuries of public underwriting and heavily protected market development. Sports organisations have been as enthusiastic about defending their independence as they have been eager to claim public funding as of right. The price for continued support by governments, players and fans must be a genuine commitment to gender equity, just as the price for the historical cosseting of men's sport should be sharing of the spoils with women.

Marginalisation and discrimination in sport bring the law into play. But sport and media organisations should lead rather than resist progressive change, and governments and the citizenry at large hold them to account. This is not a matter of charity, because the persistence of sexism in sport actually diminishes its prospects in the face of all the other items on a crowded cultural menu. Alienating half the population is a classic 'own goal' to be avoided on and off the field of play.

Further Reading

Elias, N. and Dunning, E. (1986) Quest for Excitement: Sport and Leisure in the Civilising Process. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Hargreaves, Jennifer (1994) Sporting Females: Critical Issues in the History and Sociology of Women's Sports. London: Routledge.

Hargreaves, John (1986) Sport, Power and Culture. Cambridge: Polity.

Hill, C. (1992) Olympic Politics. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Rowe, D. (2004) Sport, Culture and the Media: The Unruly Trinity (second edition). Maidenhead, UK and New York: Open University Press/McGraw-Hill Education.

Rowe, D. (2013) The Sport/Media Complex: Formation, Flowering and Future, in D. L. Andrews and B. Carrington (eds) A Companion to Sport. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 61-77.

Rowe, D. (2014a) Gender, Media and the Sport Scandal, in J. Hargreaves and E. Anderson (eds) Handbook of Sport, Gender, and Sexuality. London: Routledge, 470-9.

Rowe, D. (2014b) Sport, Masculinisation and Feminisation, in C. Carter, L. Steiner and L. McLaughlin (eds) Routledge Companion to Media and Gender. London: Routledge, 395-405.

Scraton, S. and Flintoff, A. (eds) (2002) Gender and Sport: A Reader. London and New York: Routledge.

Wenner, L.A. (ed.) (1998) MediaSport. London: Routledge.

This is the text of a panel presentation to Sports, Sexism and the Law, Western Sydney University Law School Public Seminar, Collector Hotel, Parramatta, 28 April 2016.

Posted 4 May 2016.