Killed by Death, Ashes to Ashes: Rock Stars and Mortal Masculinity

By Professor David Rowe

Early baby boomerdom has really caught up with rock music culture of late. Some famous predecessors like Brian Jones, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, and Jimi Hendrix (with a late appearance by Kurt Cobain) had joined the '27 Club' and checked out at that age.

But many of their contemporaries from the Summer of Love hadn't shared The Who's death wish, declared in their 1965 anthem 'My Generation', "hope I die before I get old".

But, with seminal rocker survivors including septuagenarian Rolling Stones and Beatles, this generation is getting old – and many of their fans with them.

With the passage of time, and in the Internet Age, we can expect a constant stream of nostalgic digital epitaphs for rock stars who symbolise lost youth and, for those born later, retro attachment.

Just after Christmas, Stevie Wright of The Easybeats died, followed in fairly short order by Lemmy of Motörhead and David Bowie of, among others, the fantastical Spiders from Mars.

All three men were born in England in the mid-late 1940s, and had seen their intense youthful party lives catch up with them in 21st century. Stevie Wright, who sang the definitive stomper 'Friday on My Mind' covered by David Bowie in the 1973 album Pin Ups, moved to Australia at age 9 and is mainly regarded as an Australian.

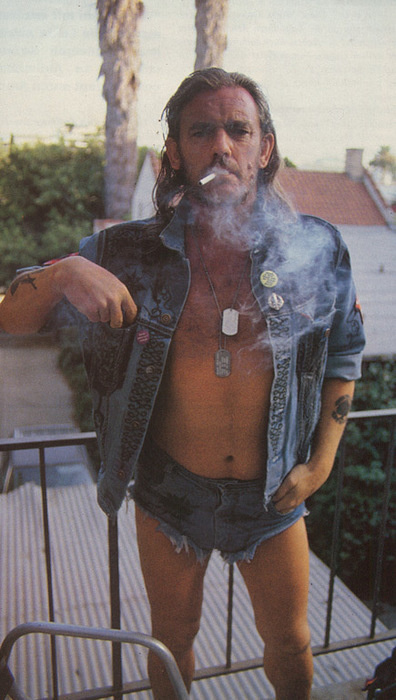

But Lemmy and Bowie, despite relocating respectively to Los Angeles and New York in late adulthood, still maintained a strong image of Englishness. They presented contrasting embodiments of English masculinity: Lemmy's working-class male aggressiveness redolent of 'The Motor-bike Boys' in Paul Willis's 1978 ethnography Profane Culture (opens in a new window), while Bowie (though also of working-class origin) rather closer to the "mannered, exaggerated, expressive style" (p. 95) of the other youth subculture researched by Willis in that book – 'The Hippies'.

Both, though, were described widely as 'English gentlemen' – for example, Lemmy "comes off as a consummately polite, older English gentleman" according to a 2009 interviewer for SPIN (opens in a new window). Bowie, similarly, in a 1978 visit to Sydney, was called "a very well-dressed English gentleman" by a guitarist of the Australian rock band The Angels (opens in a new window).

The passing of these very different exemplars of English rock masculinity bears some critical reflection.

The live YouTube commemorative service for Motörhead founder Lemmy (real name Ian Fraser Kilmister) at Forest Lawn Memorial Cemetery in Los Angeles marked more than the end of a rocker's raucous life:

In the incongruous setting of a chapel in the city where Lemmy had made his home for decades in a modest, rent-controlled apartment handy for West Hollywood's favourite hangout for musicians, the Rainbow Bar and Grill, the memorial event told us a lot about what has happened to rock culture across his allotted three score and ten years.

Lemmy managed to plug into many of the key shifts in rock music since its early stirrings in the 1950s. Born in the northern English provinces, he was a member of a requisite naff mid-60s band, The Rockin' Vicars, before taking the well-trodden road to the metropolis.

Here he became a roadie for Jimi Hendrix, who made his name in Swinging London long before Jimi was regarded as any more than a jobbing guitarist in his native US. It is ironic that, like Hendrix (opens in a new window), Lemmy was probably more revered in his adopted country than in the land of his birth.

In both cases, it helped to be something of a curiosity – Hendrix the cool African-American among the try-hard trendy Brits, Lemmy the effortlessly badass rock'n'roller among the wannabe tough guys of the various brands of US metal.

Lemmy had a particular talent for merging seemingly divergent genres of music. When he joined so-called space rock band Hawkwind in the early 1970s, he brought his conventional rhythm guitar technique to the bass guitar. The resultant driving, heavily distorted sound is evident on the band's only major hit, Silver Machine (opens in a new window), which somehow combines psychedelia with straight-ahead rock, topped by Lemmy's gruff, hitherto untried vocals.

The milder hippie ethic of Hawkwind was never going to allow an enduring connection to the amphetamine-fuelled racket generated by Lemmy, and they parted company, he claimed, over their incompatible tastes in drugs.

This was not an issue when Lemmy formed his own band, Motörhead, in the mid-1970s. The band struggled at first, but the eruption of punk played in its favour. At a time when leading punk figures like Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols and Joe Strummer of The Clash were deriding old hippies and mocking progressive rock pseuds, the speedy, noisy rush of Motörhead found a kindred sonic and attitudinal spirit.

Above: Lemmy performing with Motörhead

Once again Lemmy had succeeded in straddling competing musical styles and trajectories. Not many of his vintage would have been invited to make an appearance on the Pistols' Holidays in the Sun video, nor to collaborate with seminal punk acts like The Damned and The Ramones.

There followed a quarter of a century in which, with little obvious change in musical approach or visual style, Lemmy and Motörhead recorded and toured consistently, retaining a strong fan base, especially in the UK, continental Europe and the USA.

Indeed, his refusal to shift with the times was celebrated as authenticity rather than irrelevance. In the 2010 documentary Lemmy (opens in a new window), musicians older and younger line up to fete and sometimes to play with him. These include such male rock stars as Alice Cooper, Slash (Guns N' Roses), Mick Jones (The Clash) Lars Ulrich (Metallica), Nikki Sixx (Mötley Crüe), Jarvis Cocker (Pulp), Dave Grohl (Nirvana/Foo Fighters) and Pete Hook (Joy Division/New Order).

Although women such as Joan Jett, Stacia (Hawkwind) and Corey Parks appear and say favourable things about Lemmy – unsurprising given that it is essentially a fan-oriented film and he was given the right to pull any footage - Lemmy is a male-dominated film. It is mostly men who are in shot and speak, and there are the usual references to groupies.

The documentary also makes a good deal of Lemmy's interest in war memorabilia and Nazi insignia, as well as his notorious appetite for alcohol and controlled substances.

It was for these reasons that I was more than a little dubious when ABC's iview showed the documentary last year among its Arts and Culture offerings. Expecting to see a straight-faced version of the biting mockumentary This is Spinal Tap (opens in a new window)(1984), Lemmy (sub-titled 49% motherf**ker. 51% son of a bitch) is rather more than a dubiously uncritical portrait of a rock dinosaur casualty.

Lemmy in the film is sharp, self-deprecatingly funny and knowledgeable about various topics in and outside rock music. By staying largely in the same musical and stylistic space since well before the turn of the last century, he had seen the post-punk wheel turn and clearly emerged as a living symbol for those musicians who cherish 'keeping it real' but feel inside like fakers and copyists.

At his memorial service in the Hollywood hills – watched by legions through an online medium virtually unknown when his career peaked some four decades ago – many of Lemmy's eulogists remarked on his enduring Englishness and surprising 'gentlemanness'.

Another quintessential English gentleman, Evelyn Waugh, who had turned Forest Lawn into Whispering Glades to great comic effect in The Loved One, might have been amused to see just how far English masculinity had come since his novel was published three years after Lemmy's birth.

What Waugh, who died in 1966 when the struggling rock musician David Jones was still in the process of becoming David Bowie, would have made of the aspiring rock star from edgy Brixton is doubtful, but it is unlikely to have been favourable for the conservative Catholic novelist and snob.

Bowie was in the process of introducing androgyny to the rock world. From wearing dresses and vivid makeup to declaring himself first as 'bisexual' and then as 'trisexual', his challenge to the prevailing enforcement of constraining codes of masculinity and femininity unsettled many 'moral entrepreneurs' (as Stan Cohen had described them in his famous book Folk Devils and Moral Panics (opens in a new window)) and regular citizens alike.

Unlike Lemmy, who settled on the much more orthodox gender style of the outlaw male with a coterie of hyper-feminine groupies, Bowie's was a much more fluid aesthetic. Bowie saw himself less as innovator than synthesiser, a 'thieving magpie' who trawled the avant garde and mass culture for new angles, impressions, combinations and juxtapositions.

His was the very antithesis of the replication of a successful formula – that is, unless that formula was never to stay too long in one semiotic space, and always to move on when a sound or look became too predictable and comfortable.

Above: David Bowie (left) and Lemmy (right)

The restless career of David Bowie took him from small-time bands like the Lower Third and the Buzz to a solo career that saw him try on a range personae for size only to discard them before they signified entrapment.

Multiple earlier works and obituaries have documented his many characters, including Major Tom, Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane and the Thin White Duke. Less remarked upon, perhaps, is the tension between being a band member (although usually the front man) and a solo artist.

For example, his persistence with the hard rock band that he'd formed, The Tin Machine, in the face of much critical indifference, harked back to the times of simple male bonding with a band on the road.

Bowie also had several significant collaborations, notably with two street smart Americans, Lou Reed and Iggy Pop. His relationship with the latter is represented in barely disguised form in the film Velvet Goldmine, which can currently be viewed on SBS On Demand.

The film is set in the heart of the glam rock era, when glitter and outrageous clothes were embraced even by some formerly macho men. Iggy Pop's muscularity and confronting physical capital, made somewhat ambiguous by his glam accoutrements, render him not just an object of homosexual desire but of aspiration. Bowie, it is suggested, coveted but could not appropriate the effortless, unselfconscious, unapologetic masculine corporeality of Pop. Instead, he produced through the studio console (in various combinations) Raw Power, The Idiot, and Lust for Life, unobtrusively playing keyboards on occasion behind Pop on stage.

Of the various Bowie 'periods', it is his time in Berlin in the second half of the 1970s, which produced Low, Heroes and Lodger, that is most remembered for its artful assemblage of sound, vision, politics and place. Immediately prior to this time, Bowie had seemed (like Lemmy) to flirt with Nazi iconography, later blaming excessive cocaine use and being 'in character' as a drug addled narcissist.

But in Berlin he straightened out a little and became more productive, and his 1977 song 'Heroes' will forever be associated with the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall as its rather unlikely anthem. Bowie, in his fading years, returned wistfully to his time in Berlin, especially in the poignant 2013 song 'Where Are We Now'? (opens in a new window).

As a flaneur passing through the streets of Berlin, Bowie resembles another English gentleman abroad, Christopher Isherwood, whose 1939 novel Goodbye to Berlin inspired the stage musical and film Cabaret.

At the time of writing, there has been no Lemmy-like live-streamed memorial service for Bowie. He has reportedly been privately and quietly cremated. But a tribute has been planned in his birthplace, London, during the Brit Awards in February, and a memorial concert in March at Carnegie Hall in his adopted home town of New York.

Two very different English gentlemen of rock are presumably playing Pink Floyd's 'Great Gig in the Sky' on The Dark Side of the Moon. The unforgiving finitude of earthly life will inevitably provide many more melancholic opportunities for private and public grief.

But the abundant digital record will, equally, enable us to mine it for cultural data, memory and emotion. As Leonard Cohen wrote in 'Chelsea Hotel' of '27 Club' member Janis Joplin, "for the ones like us who are oppressed by the figures of beauty" like the perpetually shining David Bowie, there is always the consolation that "we are ugly but we have the music".

Note: 'Killed by Death' by Motörhead (1984); 'Ashes to Ashes' by David Bowie (1980).

Some work on rock and popular music by David Rowe:

- Rowe, D 1995, Popular cultures: rock music, sport and the politics of pleasure (opens in a new window), Sage, London. [Turkish translation Populer Kulturler: Rock Ve Sporda Haz Politikasi, 1996, Ayrinti Yayinlari].

- Rowe, D 2011, 'Rock culture: the dialectics of life and death', in C Rojek (ed.), Popular music, volume 3: representation and consumption (opens in a new window), Sage, London, pp. 119-28. [originally published in Australian Journal of Cultural Studies, 1985, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 127-37].