You can search for courses, events, people, and anything else.

Sustainability and Resilience 2030 is designed to be a living initiative that is open for discussion, critique and renewal and for each area of the institution to engage with this in a way that is meaningful for them.

To build collective engagement across the institution (and beyond) we have developed a suite of resources to support local conversations.

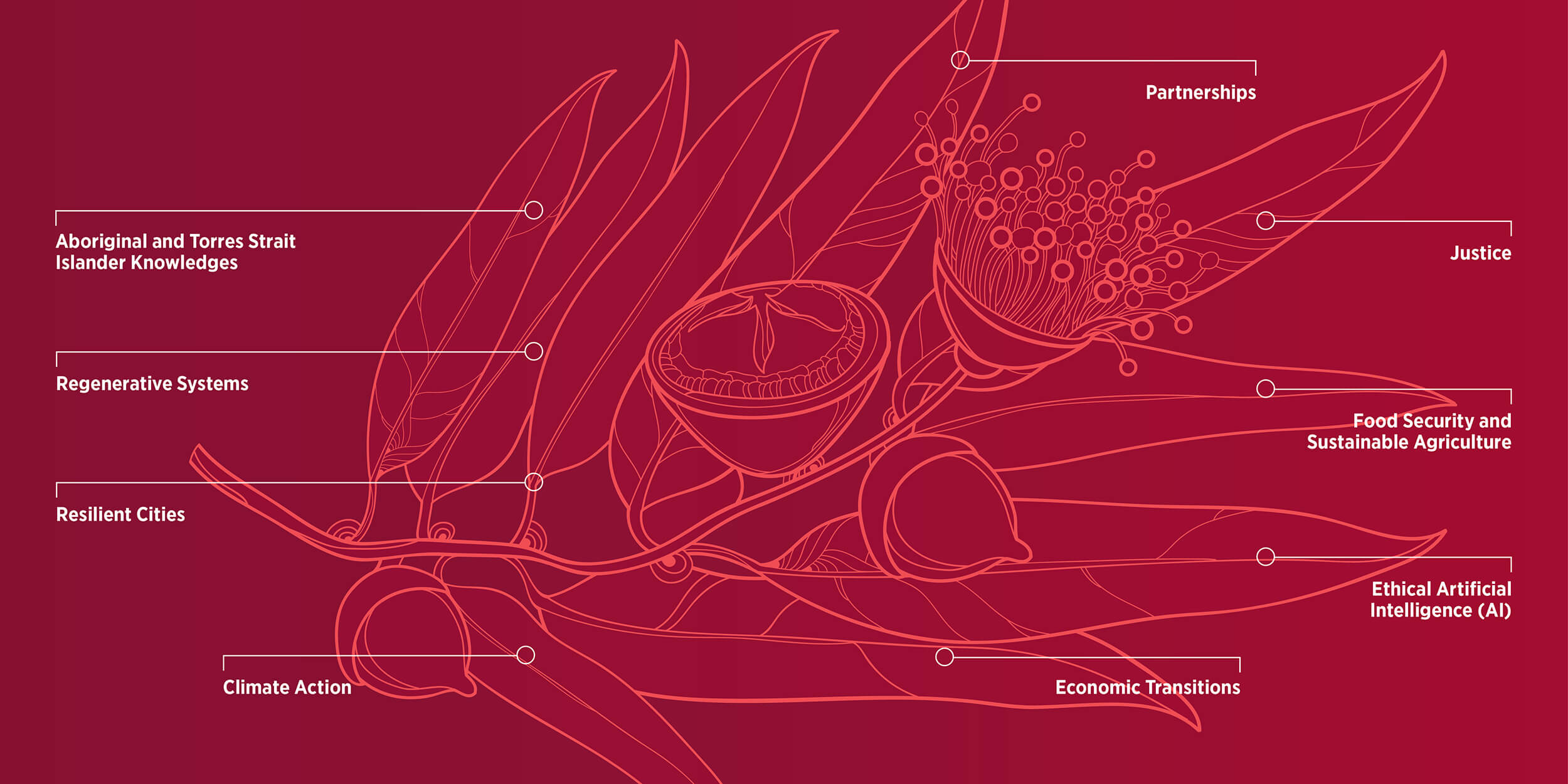

Formation of the Nine Interconnected Priority Statements

These global and regional priorities have been informed by the Regional Centre of Expertise on Education for Sustainable Development – Greater Western Sydney (RCE-GWS) network. RCEs are acknowledged by the United Nations University (UNU) in response to the United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (DESD 2005-2014) and are now mobilised to support grassroots implementation of the SDGs.

These statements are not a group of siloed priorities – progress and action on one of these themes must balance and support progress on the others. As an academic institution we do not take these as a given; the way forward should rightly be open to critical debate and discourse, although that should not prevent us from taking urgent action where the empirical evidence and our vision and values demand that we do so.

Species: Tasmanian Blue Gum (Eucalyptus globulus)

Western Sydney University acknowledges the peoples of the Darug, Tharawal, Eora and Wiradjuri nations. We acknowledge that the teaching, learning and research undertaken across our campuses continues the teaching, learning andresearch that has occurred on these lands for tens of thousands of years.

Authors: Juan Salazar and Jen Dollin

Working Group: Carol Simpson, Roger Attwater and Leanne Smith

Sponsors: Simon Barrie and Peter Pickering

Designers: Charlotte Farina and Brittany Hardiman

Aligning our Priority Statements for Local Action towards the SDG 2030 Targets

Whilst our thinking in developing the Nine Interconnected Priority Statements is wider than the SDGs, we have aligned them to the United Nations 5Ps framework: People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace and Partnerships to show where there is linkage:

PLANET

We are determined to protect the planet from degradation, including through sustainable consumption and production, sustainably managing its natural resources and taking urgent action on climate change, so that it can support the needs of the present and future generations.

PEOPLE

We are determined to end poverty and hunger, in all their forms and dimensions, and to ensure that all human beings can fulfil their potential in dignity and equality and in a healthy environment.

PROSPERITY

We are determined to ensure that all human beings can enjoy prosperous and fulfilling lives and that economic, social and technological progress occurs in harmony with nature.

PEACE

We are determined to foster peaceful, just and inclusive societies which are free from fear and violence. There can be no sustainable development without peace and no peace without sustainable development.

PARTNERSHIPS

We are determined to mobilise the means required to implement this agenda through a revitalised Global Partnership for Sustainable Development, based on a spirit of strengthened global solidarity, focused in particular on the needs of the poorest and most vulnerable and with the participation of all countries, all stakeholders and all people.

Key Inputs into the Nine Interconnected Priority Statements

As an anchor institution in the Greater Western Sydney Region, the University is part of a region that is home to the largest First Nations Australians in the country. This strategy recognises the need to position local Indigenous knowledge centrally as an integral part of the way that we respond to sustainability and resilience objectives and how we focus our research, academic and operational programs. Deep learning and the development of rich socioecological local knowledges has occurred on this land for tens of thousands of years. Indigenous knowledges and storytelling serve as an historical record, as a form of teaching and learning, and as an expression of Indigenous culture and identity.

We focus on a ‘Caring for Country’ relational approach which acknowledges that, for Aboriginal people, there is no divide between nature and culture, that Country can also be sentient and Aboriginal people can sing, talk and grieve for Country.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges have ways of knowing and being in Country that show us there is much to learn about better ways to protect and enhance biodiverse urban landscapes, riparian zones, biodiversity hotspots and green/blue corridors across Greater Sydney, nationally and globally. In the wake of the Australian bushfire catastrophe over summer 2019/20, aside from renewed public interest in cultural burning practices, Indigenous leaders have argued that Australia's bushfire crisis shows the modern approach to land management is failing and have called for a new workforce of 'fire practitioners' to implement traditional burning practices across Australia. Our strategy responds to this call with our first priority statement.

The second framing of this strategy draws on accounting for socioeconomic growth within the principles of Planetary Health. Planetary Health is an emerging academic discipline that is grounded in understanding of the interdependence of human and natural systems. Notably, understandings of connections between land, culture and health are not new for Indigenous people. Indeed, they are foundational in Indigenous spirituality and contemporary cultural practices. The subtle interaction of the tangible and intangible aspects of Ngurra (Country), and the profound role it plays in the lives of Traditional Owners, can offer wider insights into how human societies could better thrive.

The objective of a Planetary Health approach is to enable transitions to more sustainable patterns of urban development and management, to foster livelihoods, and more general ways of living, that are in harmony with nature. This approach safeguards the health and wellbeing of Western Sydney citizens through good stewardship of the region's unique natural systems, embracing more sustainable food systems, affordable energy and housing, and acting in more integrative ways to respond effectively to existing and new health challenges. A Planetary Health approach commits us to developing regenerating systems and processes for our landscapes and ecosystems.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by all United Nations Member States in 2015, outlines 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which are an urgent call for action by all countries – developed and developing – in a global partnership. The SDGs supersede the Millennium Development Goals established in 2000 and build on decades of work since the 1970s by the United Nations.

The University’s Sustainability and Resilience Decadal Strategy leverages the United Nations SDG 2030 Agenda to input into the definition of our Nine Interconnected Priority Statements. The University has achieved extraordinary results in the Times Higher Education Impact Rankings in 2025 as a platform for delivering against this strategy.

One of the most innovative and far-reaching aspects of the SDG 2030 Agenda is that it recognises the interlinkages between and within the goals, and the need for them to be addressed as an indivisible and integrated whole. Given the complexity of interactions between the goals, and the siloed ways in which many actions are undertaken, this is also one of the hardest aspects of the SDGs for policy and decision-makers to implement.

Our strategy is an attempt to adapt these goals to the reality of our Western Sydney region and our University’s purpose in supporting the development of sustainable and resilience practices within the region. We recognise the limits of the frameworks that we have outlined above, and the establishment of our priority statements has also been guided by the principles of

- Criticality

- Contestability

- Uncertainty

- Connectivity

- Co-design, co-construction, and collaboration

COVID-19 Pandemic Considerations

The global COVID-19 pandemic triggered in 2020 has opened a crevasse in our security and our sense of continuity and order. The cascading economic impacts have been severe with many countries ‘suffering indirect consequences from value chain disruptions, historical unemployment, and lower international demand for goods due to widespread recession’.28 The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has described this shrinkage in the global economy as the most severe since the Great Depression of the 1930s. In April 2020 the IMF called for increased investments in health care systems, financial support for workers and businesses, continued central bank support and a clear exit plan for the recovery.

Scientific studies have proven that like other pandemics in the past 20 years, COVID-19 is a consequence of how humans interact with animal worlds and natural habitats.30 Unrestrained production and consumption patterns including human - wildlife conflicts and industrial farming systems expose humans to unknown pathogens. We must gauge the extraordinary seriousness of the social, ecological, political and economic effects of this pandemic and look for new ways forward that genuinely reshape institutional, regional, national and global systems that recognise the interdependence of all life. The link between pandemics, natural disasters, climate change, biodiversity extinction, racism and social justice has been made explicitly clear.

This confluence of local and global environmental, health, economic and social crises presents an opportunity for deep reflection and a commitment to meaningful change. In a context of COVID-19 recovery, this strategy proposes thinking collectively about how best to move beyond the narrative that Western Sydney is the nation’s third largest economy and fastest growing region.

This fast growth has brought immense benefit for some sectors, but it is not sustainable. CEDA (Committee for Economic Development Australia) has reported that ‘despite 26 years of uninterrupted economic growth Australia still has large pockets of disadvantage with 13% of Australia’s population living below the poverty line’.

The Global Sustainable Development Solutions Network, of which the University is a member, in conjunction with Fairtrade Australia and New Zealand and the Global Compact Network Australia have released a 5-point plan for regional and global recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. This aims at reducing inequalities and building a more resilient economic future and calls for:

- Achievement of the SDGs by 2030;

- Coherent policies and market mechanisms that support innovation and move Australia to net-zero emissions by 2050;

- Multilateral and regional partnerships to drive economic recovery, build environmental resilience and enhance regional outcomes;

- Investment in fair, transparent and more inclusive trade; and

- Reduced structural inequalities to protect and support the most vulnerable.

Key Definitions and Terms

At Western Sydney University we acknowledge that sustainability and sustainable development is an ethical philosophy as well as a practice and as such definitions are diverse and contestable. This should be considered a key strength, in that the concept and values can be discursively ‘created’ rather than authoritatively ‘given’. All definitions of sustainability and sustainable development, however, do agree on the concept of limits in a finite world. The Club of Rome 1972 report ‘The Limits to Growth’ was a critical document that shaped ensuing debates and identified for the first time a global concern with three potential kinds of limits:

- Ecological limits to the physical scale of economic activity;

- Limits to the economic welfare to be derived from growth of economic activity; and

- Social limits to economic growth.

These debates were also captured in the 1987 Brundtland Report ‘Our Common Future’, commissioned by the United Nations Commission on Environment and Development. This report has not only set the agenda for the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) almost 30 years later, but also outlined a vision of development based on allowing future generations to meet their own needs.

This was the first agreed definition of sustainable development:

”Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. It contains within it two key concepts: the concept of needs, in particular the essential needs of the world's poor, to which overriding priority should be given; and the idea of limitations imposed by the state of technology and social organization on the environment's ability to meet present and future needs.”

This definition brought into global debate the concepts of needs, wants and inter-generational equity. A more recent definition that is widely used expands the term to ‘just sustainability’:

‘‘Just Sustainability’ refers to the importance of ensuring “a better quality of life for all, now and into the future, in a just and equitable manner, while living within the limits of supporting ecosystems.”

The international field of ‘Education for Sustainability’ (EfS) or Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) has emerged in response to urgent requirements for critical global citizenship and the original framing came from the Bruntland Report. EfS and ESD puts emphasis on the necessary interrelationships between theory and practice, local and global scales, and present and future, and thus has a global citizenship component that requires a critical evaluation of environment and social justice issues. EfS/ESD curriculum requires an understanding of ontology, epistemology, axiology and ethics.

“EfS is a lifelong learning process that leads to an informed and involved citizenry having the creative problem-solving skills, scientific and social literacy, and commitment to engage in responsible individual and cooperative actions. These actions will help ensure an environmentally sound and economically prosperous future."

Resilience thinking considers that culture and nature are strongly coupled as part of one social- ecological system and is based on the core understanding that humans are not inseparable from their environment. Similar to ‘sustainability’ definitions, resilience definitions have been subject to debate and are diverse. The Stockholm Resilience Centre, a non-profit, independent research institute specialising in sustainable development and environmental issues, has been leading this work since it was founded in 2007.

“Resilience is the capacity of a system, be it an individual, a forest, a city or an economy, to deal with change and continue to develop. It is about how humans and nature can use shocks and disturbances like a financial crisis or climate change to spur renewal and innovative thinking.”

In an attempt to define a scientifically-derived safe operating space for humanity that can assist decision makers, researchers have developed the concept of planetary boundaries. In 2009 a group of leading international scientists identified that there are nine planetary boundaries that humanity needs to stay within to develop and thrive for generations to come. Crossing these boundaries could generate abrupt or irreversible environmental changes. In 2015 updated research warned that four of the nine planetary boundaries have been crossed as a result of human activity: climate change, loss of biosphere integrity, land-system change, and altered biogeochemical cycles (phosphorus and nitrogen). Two of these, climate change and biosphere integrity, are what the scientists call ‘core boundaries’ and altering either of these would drive the Earth System into a new state.

The nine planetary boundaries are climate change, stratospheric ozone, ocean acidification, nitrogen and phosphorus cycles, biodiversity loss, land use change and freshwater use.

“A just transition for alltowards an environmentally sustainable economy…needs to be well managed and contribute to the goals of decent work for all, social inclusion and the eradication of poverty.”

The Just Transition Alliance defines ‘just transitions’ as a principle, a process and a practice.

The concept is for a unifying, place-based set of principles, processes and practices that shift systems from an extractive economy to a regenerative economy. This means challenging traditional linear production and consumption cycles and moving towards holistic and circular economy models. A leading principle is that the transition itself must be just and equitable; acknowledging and repairing past harms and developing new relationships of power. Just Transition strategies originate from the labour unions and environmental justice groups. Low income communities and workers define a transition away from polluting industries that were harming workers, community health and the planet; and at the same time provide just pathways for workers to transition to other jobs.