Delivering Better Birthing Strategies

You can search for courses, events, people, and anything else.

In her first year of school at Campbelltown North Public School, Mindy Taylor is flying. With her proud mother Tina watching, she was called on to the assembly stage to receive an honour badge for her academic efforts.

“The principal was blown away by Mindy’s work and said, ‘You see her writing, she’s amazing’,” Tina recalls. The Indigenous mother of three girls under the age of seven considers it a miracle that her daughter, who spent the first days of life in intensive care, has thrived.

Mindy’s health, and engagement with learning, as well as Tina’s confidence in her parenting, is partly due to her involvement in a unique child and family health nurse home visit programme that is making an impact around the globe.

Before the birth of her first baby, Tina was approached to join the Bulundidi Gudaga (‘healthy pregnancy, healthy baby’) Maternal Early Childhood Sustained Home visiting (MECSH) programme for Aboriginal families in the Macarthur region, in south-west Sydney.

Although she had her husband, father and sister, Tina says her first pregnancy was an emotional time because it made the absence of support from her mother, who had died four years earlier, feel more acute.

“It was the first I’d heard of the home visit scheme,” she recalls. “The other women in my mothers’ group all had to make appointments to go to the doctors and weigh-ins, while I had the nurse coming to my home.

I didn’t realise how easy it made having a baby until I heard other mothers’ stories.”

The weekly home visits in the early days of Mindy’s life were also critical for Tina’s mental health, having been through an emergency caesarean and traumatic birth. “Having them visit and talking to them was great because it is quite lonely being at home with a child. They knew my story so I didn’t have to keep retelling it,” she says.

Tina’s reflections are no surprise to Western Sydney University Distinguished Professor of Nursing Lynn Kemp, an international leader in the field of early childhood interventions in primary and community health and translational research. As the founder of MECSH, she has witnessed the benefits of the home visit programme for children like Mindy.

Like many of its clients, MECSH was born in difficult circumstances.

By the end of the 1990s, some societal structures were fractured in the Sydney postcode region of 2168 that centered on the suburb of Miller, just 38km south-west of Sydney’s CBD.

“There was unrest. The local community health centre got firebombed, most of the shops shut down, the police station moved, and the only GP in the area closed down,” Kemp recalls. “Even Pizza Hut wouldn’t deliver because kids were throwing rocks at the drivers.”

Through all the chaos, child and family health nurses continued to have access to families living in the area, and retained their trust.

In response to the social fragmentation, the NSW Government allocated money for community solutions, under which Kemp was tasked with finding ways to improve health and wellbeing outcomes for children aged up to two years.

“We knew that the only people getting in the door were the child and family health nurses,” says Kemp. She devised the key approach that differentiates MECSH from other programmes: “I realised that MECSH would be better if it was embedded in existing services and improving their capacity, rather than setting up something separate,” she says.

Need to know

- MECSH stands for Maternal Early Childhood Sustained Home visiting programme

- It is embedded into existing services and builds up their capabilities

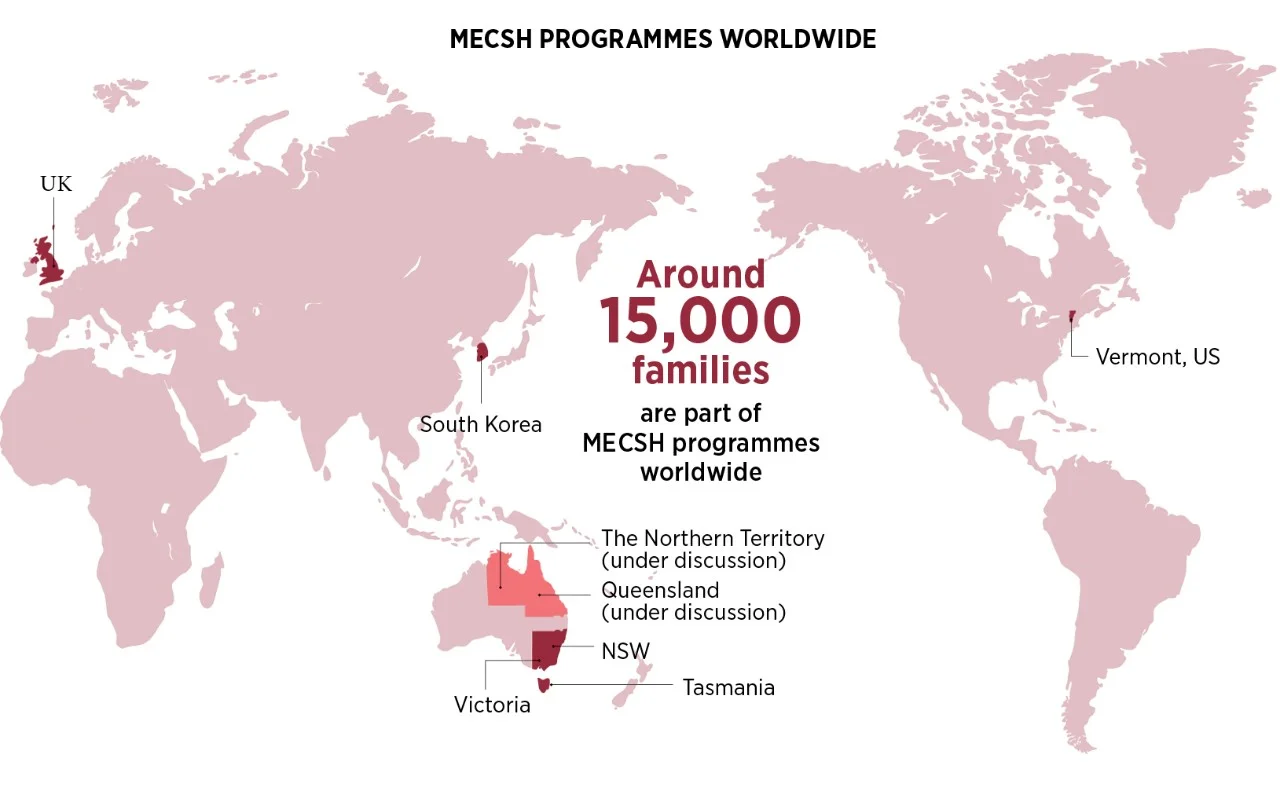

- It has helped around 15,000 families across Australia, the UK, the US and South Korea

The MECSH programme set up by Kemp and her colleagues at Western Sydney University, University of NSW, Macquarie University, and local health services, saw nurses regularly visiting the homes of pregnant women up to eight weeks before their child was born, to help prepare them for parenthood. Then continue those visits until their child turned two.

At the time, Kemp’s team only had enough funding to provide the programme to 50% of eligible families, creating the perfect conditions for a randomized control trial.

The trial results were striking. New mothers involved in the MECSH programme were more likely to have a vaginal birth and felt more confident to care for their baby and themselves, and created a home environment that was more conducive to their child’s cognitive development. The babies in the trial were breastfed for longer, met developmental milestones, and had stronger engagement with their mothers.

Tina’s experience reflects these results. Where many of her friends weaned their babies at four months, she breastfed all three children to six months and was supported by the child and family health nurse to feed the babies home-cooked food when they weaned.

“I’ve never fed the girls packet food because the nurses helped show me how to prepare fresh food and how to store it,” she says.

Likewise, Mindy’s success in her first year of school mirrors the results of the original MECSH babies as they began school life. Serendipitously, the trial cohort started school in 2009, coinciding with the first Australian Early Development Census. The census showed that children in the 2168 postcode met, or bettered the national average in school performance.

For Kemp it was an outstanding validation of their work. “We know that the sensitive period in brain development for all domains occur in the first two years, it is a really critical period for laying the foundations for language, social development and emotional control,” she says.

“[Prior to MECSH] You would have expected these children to be doing poorly, but these children were equal to, or better than, the national average, so the programme clearly does have long-term and community-wide impact.”

Kemp believes these impacts are the result of how the programme is embedded into existing services. “One of the important things about MECSH is that the training is provided to all nurses in the service. The skills then spill over into the way nurses work with every family so we get a whole community effect.”

Beulah Lewis, who oversees MECSH implementation in Lewisham, in the United Kingdom, believes the flow-on impact is one of MECSH’s strengths. “One advantage that staff recognised immediately is that the MECSH training and tools can be applied across all families, not just families recruited to MECSH. Early identification of further need is a key outcome of the programme delivery which enables effective targeting of resources and onward referrals to support a family’s health needs,” she says.

After receiving US federal government accreditation, MECSH began to attract global interest and is now operating in Vermont in the United States, as well as in the UK, and in South Korea. In Australia it is being rolled out across NSW, Victoria and Tasmania, and discussions are underway to implement MECSH in the Northern Territory and Queensland. It is estimated that around 15,000 families are part of MECSH programmes worldwide. In South Korea, Kemp’s work has been instrumental in the establishment of a universal child and family health service system, which includes the MECSH programme, serving the city’s 10 million residents, where previously families had no access to such support.

Young-Ho Khang, director of the support team for the Seoul Healthy First Step Project, and a Professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management, Seoul National University College of Medicine, says a key factor in adopting the MECSH programme was its ability to address health inequalities by delivering help as needed. “MECSH is not a cookbook in home visitation,” Khang says. “MECSH takes into account local situations. It could be applicable in many settings and thus could meet the needs of local areas.”

Ann Giombetti, from the Division of Maternal and Child Health, in Vermont’s State Department of Health, agrees. “It is designed specifically to coordinate and collaborate with Vermont’s statewide system of referral for families with young children,” she says. “This model also allows for more flexibility with regard to enrolment criteria and enables our communities to enrol at any point during pregnancy, including up to six weeks postpartum.”

Kemp is not surprised by its adaptability. “MECSH changes everywhere it goes. It is designed to embed and build the capacity of the local service system and local communities,” she says.

Fifteen years after MECSH was launched, Kemp’s goal continues to grow. “My personal driver is that no child on earth has their opportunities limited by the circumstances into which they are born and live,” she says, laughing at her vast ambition. “I can say to myself that at the end of every day, I feel like I’ve chipped away at my goal and that there is one more family being supported, one more community that is engaged.”

Meet the Academic | Distinguished Professor Lynn Kemp

Dr Lynn Kemp is recognised as an international leader in the field of early childhood interventions in primary and community health and translational research. Her local, national and international research in early childhood is bringing quality evidence-based early intervention programs to vulnerable families with young children in Australia and world-wide.

Lynn’s work is leading translation of research findings into population-scale programs. Through the MECSH programs nurses working with families have, as described by one nurse, "a great opportunity to facilitate some changes, empower families to find a way forward that might be different from their past." Her skill in supporting population scale implementation is now also informing strategies for improved adoption of effective cancer and volunteer interventions. Lynn is an academic leader graduating 14 PhD students since 2008, and an honorary fellow at Kings College London.

Related Articles

Credit

This research was supported by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council and the National Health and Medical Research Council.

© Tania Bondar/ Getty Images

Future-Makers is published for Western Sydney University by Nature Research Custom Media, part of Springer Nature.