You can search for courses, events, people, and anything else.

A study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic has found that Asian Australians are overwhelmingly not reporting incidents of racism, and Associate Professor Nida Denson from Western Sydney University’s School of Social Sciences is trying to find out why.

Denson, who was born to Thai immigrant parents in the United States and grew up in the Midwest, aims to improve the health and wellbeing of marginalised groups by understanding how racism occurs at the individual and organisational level.

While completing her PhD at UCLA in the United States, her work was focused on diversity in higher education contexts and has appeared as evidence in U.S. Supreme Court cases supporting race-conscious university admissions practices. Since joining Western in 2007, her research interests have expanded to include racism in broader contexts. Denson is also a member of the Centre for Resilient and Inclusive Societies, an independent think tank comprised of universities and civil organisations undertaking research to inform policies for social inclusion and resilience.

As part of a project stream that aims to challenge racism and enhance social belonging, Denson co-led a study with Western colleague, Dr Alanna Kamp, a senior lecturer in the School of Social Sciences, to conduct a nationwide survey of more than 2,000 Asian Australians about their experience during COVID-19. In November 2020, the researchers asked participants about their experiences of racism before March 2020 — when the first lockdown began in Victoria — and how their experiences had changed since then.

Need to know

- Asian Australians experienced many racist incidents during the pandemic.

- They were unlikely to report this due to a lack of trust in authorities.

- Nida Denson and colleagues are launching a campaign called Let’s Talk about Racism.

"I’m sure that if I reported the incident, it would have been ignored. Even worse, I feared that I would have to face ramifications for reporting the incident."

LACK OF TRUST

A startling revelation was that many racist incidents during this period went unreported to authorities, employers, friends or family. While overt acts of racism decreased by 10% in Victoria — which had undergone the longest lockdown at the time of the study — and 8% across the nation due to lockdowns and physical distancing, 40% of Asian Australians still faced racism during the pandemic.

Furthermore, on asking victims about their likelihood to report racist incidents, 30–50% chose not to report racism they faced or witnessed, even to friends and family. Only 3% of victims and witnesses reported racism to the Australian Human Rights Commission, implying that the number of complaints received by the Commission underrepresents reality.

"Not reporting was the most common response. This was for many reasons — some didn’t have knowledge of authorities they could report to. Others thought authorities just would not care, and that they would be re-traumatised through reporting," says Denson. "The results show that 63% of respondents believed that their report would not be taken seriously, 60% felt the incident would not be handled in an appropriate manner, and 40% lacked trust in authorities. That was surprising and sad."

One respondent shared that the offender was a client of their employer. "I’m sure that if I reported the incident, it would have been ignored. Even worse, I feared that I would have to face ramifications for reporting the incident," they said.

The anticipation of racism left a significant impact on Asian Australians’ mental health, even for those who hadn’t been direct victims of racism. "Over three quarters of respondents said that they avoided going outside for things like shopping, even after lockdowns were eased," says Denson. "The anxiety from anticipating racism eroded their mental wellbeing, and also affected their sense of feeling Australian and their sense of social cohesion."

NEW WAYS OF COHESION

Drawing on these learnings, Denson and colleagues are launching a social media campaign (Let’s Talk About Racism) to educate the wider community on what racism could look like, both overt and subtle. The campaign will use social media tiles and a short video to depict these scenarios and provide specific suggestions for actions that victims and bystanders can take.

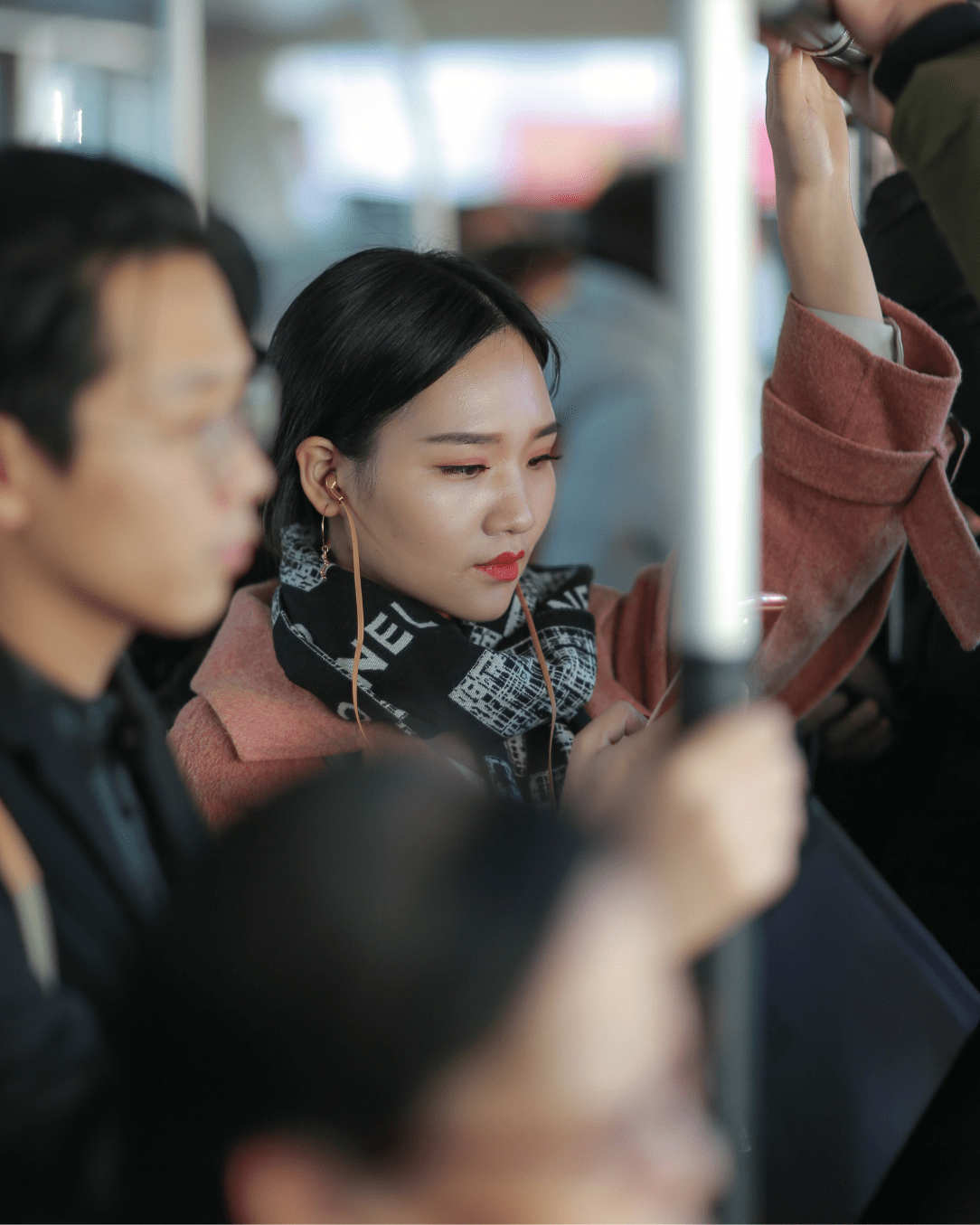

"There have been instances on public transport where an individual openly berates an Asian person, but the rest of the passengers sit in silence, unsure of what to do. From the perspective of the victim, this can feel like the other passengers agree with the aggressor," she says. "In instances like this, bystanders can ask whether the victim is OK. They don’t have to confront the perpetrator, but it’s important to recognise that bystanders can be a more active participant; it shouldn’t be left just to the victim to stand up, because they’re not always able to."

While Denson believes racism will always be an issue, she sees hope from marginalised groups learning from each other and coming together. "The target of racism changes based on world events. Islamophobia was huge after 9/11, and now with COVID-19, Asian hate," says Denson. "For example, Islamophobia Register, a group that began creating a platform for people to report incidents of Islamophobia, is seeking cross-group collaboration; groups combatting Asian Hate are thinking of creating a similar register. Change is gradual but underway," she says.

Meet the Academic | Associate Professor Nida Denson

Nida Denson is the Associate Dean, Higher Degree Research and an Associate Professor in the School of Social Sciences. Her research aims to combat racism and discrimination, and to improve the health and wellbeing of various marginalised groups (e.g., people of colour, people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, people who are gender and sexuality diverse). She brings to her work an interdisciplinary focus that promotes new understandings. By blending psychological insights into her social sciences research, and applying quantitative methods through a psychological perspective, she bridges disciplines to yield innovative and impactful solutions to complex societal challenges.

She is currently a Chief Investigator on two ARC projects and other nationally competitive grants, projects and tenders. The ARC Linkage Project (where all four chief investigators are migrant women of colour) examines place-based employment and enterprise of newly arrived young migrant women in Southwest Sydney. The ARC Discovery Project examines online anti-racism and complements her other Centre for Resilient and Inclusive Societies (CRIS) think-tank consortium project on emerging vectors and sources of racism.

In collaboration with colleagues from the CRIS consortium, she published the first comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis on racism as a determinant of health. It has been cited over 2300 times (Google Scholar, January 2024) and is in the top 5% of all research outputs scored by Altmetric. She is internationally recognised for her anti-racism work in higher education, with her research being cited in U.S. Supreme Court Cases as evidence supporting race-conscious admissions practices as well as anti-racist education in American schools by the American Educational Research Association (AERA) and the National Academy of Education.

Credit

Future-Makers is published for Western Sydney University by Nature Research Custom Media, part of Springer Nature.

© Wachiwit/iStock/Getty

© rawpixel.com/Freepik

© 全 记录/Pexels