You can search for courses, events, people, and anything else.

Tara Roberts, an associate professor of oncology at Western.

Tara Roberts is a born scientist. "According to my mother, the first word to come out of my mouth was 'why'," she says. "I’ve always been interested in the world around me and in how things work."

She started to focus her curious nature on biomedical research while still in high school, when her grandmother was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. "The treatments she was offered weren’t effective and caused side effects," she recalls, "I quickly realised how little was known about the disease and the need for more research into better treatments."

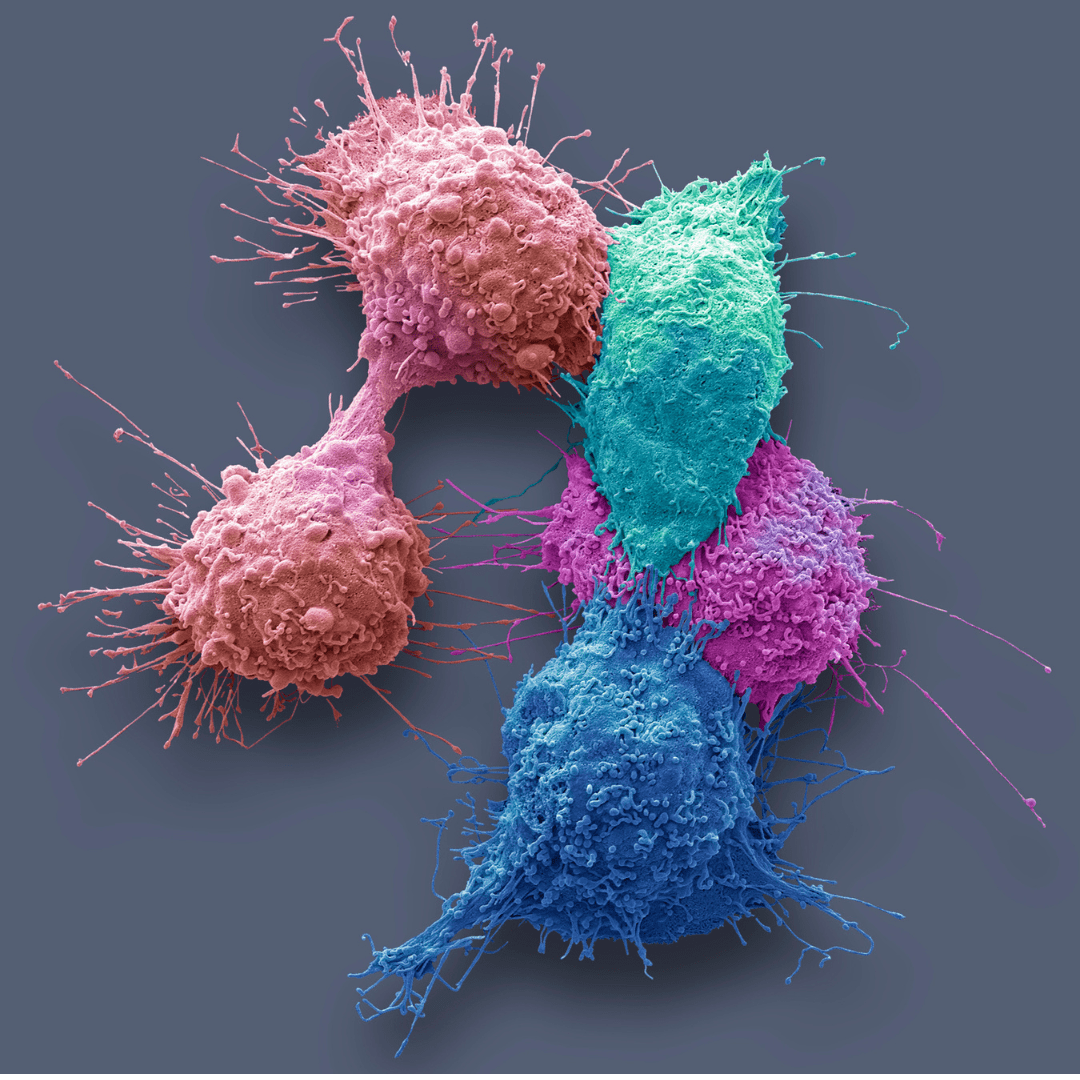

Roberts is now an associate professor at Western Sydney University, where she leads a research group that focuses on examining the role of inflammation in cancer development and progression.

"We are currently pursuing two lines of research," she explains. "One aims to predict how cancer patients will respond to immunotherapy, and the other is looking at DNA-damaging therapeutics and how they can be used to stimulate anti-tumour responses." The ultimate goal of the group is to personalise cancer therapy and improve patient outcomes.

IMMUNOTHERAPY HOPE

Treatments that boost the immune response against cancer cells, referred to as immunotherapies, are offering new hope to some patients. "A subset of patients respond brilliantly and are practically cured from metastatic disease, which is something we didn’t think we’d be able to say a decade ago," Roberts says.

However, many patients do not respond. Roberts’ group is trying to work out what makes a patient 'the right one' to receive immunotherapy and ways to extend the benefits of immunotherapy to more patients.

She has recently embarked upon a large collaborative project that combines several novel techniques to characterise the molecular signalling pathways that are activated in circulating tumour and immune cells collected from patients' blood.

"Liquid biopsies allow us to gather more timely information about a cancer and are easier to perform than tissue biopsies," she explains.

Working with the Cancer Systems Microscopy lab at UNSW, led by Dr John Lock, Roberts is using a platform that enables the detection of multiple protein markers simultaneously, right down to the resolution of single cells.

"By gathering a comprehensive picture of what cancer cells and immune cells are doing over time, we will be able to select patients who are best suited for immunotherapy, determine when they are becoming resistant to treatment, and make better therapy choices," she says.

In some cases, treatments that prepare or support the immune system before or during immunotherapy, can make immunotherapy more effective. During her postdoctoral research, Roberts found that DNA damage can trigger the release of DNA from the nucleus into the cytoplasm, where it can trigger pro-inflammatory signalling.

"This response has been well characterised in the context of infection," she explains. "But what we’ve found out since then is that it may be possible to manipulate radiotherapy, which breaks up the DNA inside cells, to boost responsiveness to immunotherapy."

Need to know

- Not everyone responds to cancer immunotherapy.

- Western’s Tara Roberts is trying to find out what makes specific patients respond to it.

- This could help personalise cancer therapy.

"A subset of patients respond brilliantly and are practically cured from metastatic disease."

GROUNDBREAKING WORK

Weng Ng, a medical oncologist at Liverpool Hospital, has been working closely with Roberts to identify biomarkers that predict prognosis and treatment response in patients with gastrointestinal cancers. Their collaboration has resulted in successful funding proposals and numerous publications.

"Roberts' research into cytosolic double-stranded DNA sensing is groundbreaking and will have a major impact on improving the care of cancer patients," Ng says.

Roberts envisions being able to carry out more comprehensive analyses of patient data with the assistance of AI and machine learning. "Combining emerging knowledge of the molecular signatures of cancer with other types of data, such as imaging and patient notes, will help us move away from a 'one-size-fits-all' approach and towards treatments tailored to individual patients," she says.

In addition to leading a research group, Roberts teaches oncology to undergraduates at Western’s School of Medicine and is the Associate Dean of Higher Degree Research for the School of Medicine, providing academic leadership and strategic direction to the higher degree research programmes at the University. "Balancing all these roles can be challenging, but it is very fulfilling to work towards transforming patient care," she concludes.

Meet the Academic | Associate Professor Tara Roberts

Tara Roberts is an Associate Professor of Oncology and the Associate Dean, Higher Degree Research at the School of Medicine. She is also the current Irene and Arnold Vitocco Cancer Research Fellow at The Ingham Institute for Applied Medical Research. Tara completed her PhD in 2005 at the University of Queensland examining immune responses to DNA. She was awarded an NHMRC Peter Doherty Fellowship in 2007 and moved to The Queensland Institute of Medical Research studying the role that inflammation in cancer and neurodegeneration. In 2014 she accepted a Cancer Institute New South Wales Future Research Leader Fellowship to move to The Ingham Institute and Western Sydney University. Here she established the “Cancer and Inflammation” laboratory whose members research lung, gastric, prostate and colorectal cancer, as well as immunotherapy, liquid biopsy and DNA damage. Tara’s research has a strong translational focus (bedside to bench and back again) including the training of clinician researchers. Through this work she and her group aim to understand how individual characteristics of each patient and their tumour can be used to personalise cancer treatment and improve outcomes for cancer patients.

Credit

Future-Makers is published for Western Sydney University by Nature Research Custom Media, part of Springer Nature.

© Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library/Getty

© Nguyễn Hiệp/Unsplash

© Ingham Institute