Could faecal transplants save koalas?

You can search for courses, events, people, and anything else.

When a koala dubbed Bingara Liz was admitted to the Port Macquarie Koala Hospital, she was in a bad way. Suffering from a severe case of chlamydia, her eyes were red and almost swollen shut. She was put on a course of intravenous and topical antibiotics to treat the infection.

Liz is just one of many koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) treated for chlamydia in wildlife hospitals every year. The Australian Koala Foundation estimates perhaps 20,000 koalas have been treated in facilities such as the Koala Hospital since the mid-1990s. As few as 20% survive their treatment.

“They’ll be on the antibiotic and the chlamydia will be starting to clear up, but then the animal crashes,” says Dr Michaela Blyton, formerly a research fellow at Western’s Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, who is now based at the University of Queensland. “The assumption has always been that the antibiotic treatment has wiped out their useful gut bacteria and they’re not digesting food appropriately. They stop eating and they just go downhill.”

Research from Blyton, and her Western Sydney University colleague, Associate Professor Ben Moore, could lead to a new treatment for koalas to counter the harmful effects of the antibiotics, boosting their chance of survival.

With the animal listed as endangered in New South Wales, Queensland and the Australian Capital Territory as of February this year, the survival rate of koala hospital patients is important to the species’ success in those states.

Moore and Blyton profiled the diversity, abundance and activity of koala intestinal bacteria revealing an astonishing, complex relationship between koalas, their food and their microbes. They also found that the microbial community of a koala’s intestine can be artificially altered.

Moore started down the unusual path of examining koala faeces because he noticed that when koalas ate manna gum leaves (Eucalyptus viminalis), their preferred food tree, and stripped them bare, most individuals did not switch to feeding on the less preferred messmate (E. obliqua) trees nearby.

Moore wondered whether their microbiome played a role.

He and Blyton designed an experiment to test whether koala feeding had any relationship to their gut bacteria. Along with collaborators, they captured koalas from a manna gum forest and kept them for two months, collecting their faeces and running DNA sequencing on it to identify the resident bacterial species and their functions.

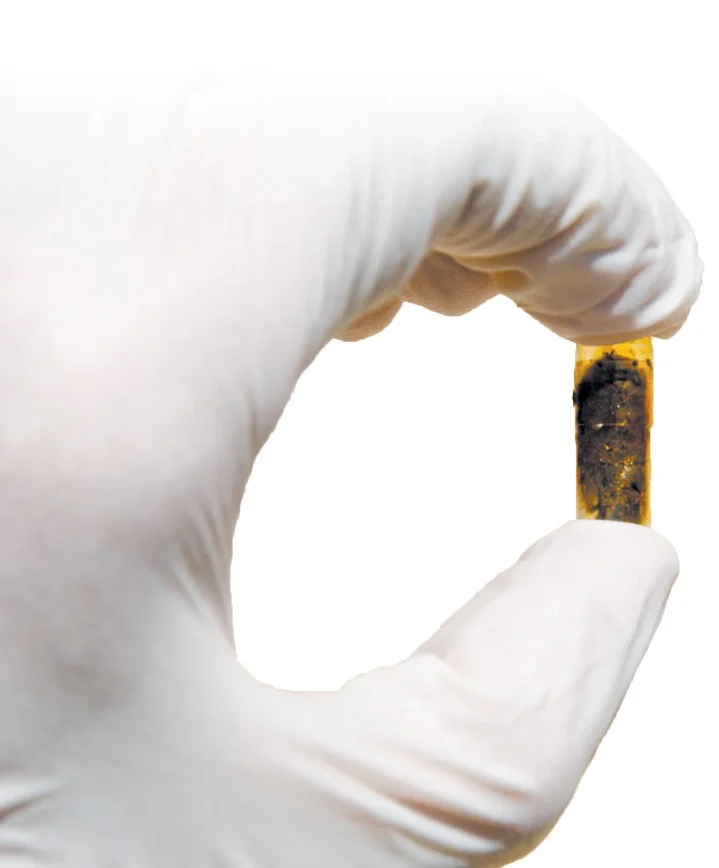

By night, the marsupials were given an abundance of messmate leaves; by day, they were offered manna gum to ensure they would still feed. For nine days, the animals were also administered two daily probiotic pills. Some were dosed with the bacteria extracted from the faeces of messmate-eating koalas living in the wild that had been previously caught; others were inoculated with their own manna-gum-conditioned bacterial community.

Need to know

- Researchers have profiled the gut bacteria of koalas

- Research found that gut bacteria communities can be artificially altered

- Probiotic pills for sick koalas could be derived from this work

When Blyton looked at the results of the DNA sequencing, she found that more than 80% of koalas had experienced a shift in their microbiomes due to their messmate diet and probiotic course. “Some shifted a lot, while others shifted a bit — their microbiomes became more similar to those of the messmate-eating donors,” she says.

Curiously, the researchers also found that the degree of change in the microbiome determined how much messmate they ate.

“The more the microbiome shifted, the more messmate an animal was willing to eat,” says Blyton.

While Bingara Liz survived her experience on antibiotics, many koalas don’t. The researchers hope their work could ultimately lead to a koala-specific treatment, practical for regular use, that could help maintain the delicate balance of intestinal flora during and after a course of antibiotics.

In 2019 Blyton and Moore published their findings in Animal Microbiome. “There is now wide recognition of the importance of the koala’s microbiome to local dietary specialisation and health,” says Moore.

Along with Professor Phil Hugenholtz from the University of Queensland, Moore and Blyton are now exploring the possibilities for koala microbiome manipulation in more depth. “We’re hoping to gain a better understanding of which microbes are most important to koalas’ digestive health, what their contribution is to the effective digestion of plant fibre, and most importantly, how these microbes can be isolated and preserved for distribution to koala carers throughout Australia,” says Moore.

“It’s important in terms of conservation biology, not just helping a few little animals that are sick on the sidelines,” says Moore. “There are enough seriously threatened koala populations in New South Wales and Queensland where a substantial part of the population is coming into care. Losing those animals from the population is actually dooming the survival of those populations in the wild. We need to get them out of the hospital and back into those wild populations.”

More Information

Meet the Academic | Associate Professor Ben Moore

Ben Moore is an ecologist broadly interested in plant-animal interactions, chemical ecology and the causes and consequences of variation in plant chemistry. He is particularly interested in the chemical, nutritional and physiological ecology of Australian marsupials, like the koala, that feed on Eucalyptus. What adaptations and strategies have these animals adopted that allow them to survive on this challenging diet? How is climate and landscape change altering the ecology of these interactions? And how does the quality of Eucalyptus as food for herbivores vary across the landscape and through time?

Ben completed his honours degree in zoology at the University of Melbourne and then obtained his PhD from the Australian National University (Canberra). He then spent 2.5 years at James Cook University in Townsville and 5 years at the James Hutton Institute in Aberdeen, Scotland.

Related Articles

Credit

This research was supported by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council.

Future-Makers is published for Western Sydney University by Nature Research Custom Media, part of Springer Nature.