You can search for courses, events, people, and anything else.

When did you last notice the trees in your neighbourhood? Perhaps it was on a scorching summer afternoon when you took advantage of the cooling shade they provided, or when you stopped to shelter beneath their leafy canopy during a downpour. Was it when you looked up to track the source of a burst of bird calls and realised the branches above you were alive with lorikeets? Or when you stopped to admire a town boulevard painted with living autumnal colours?

Trees are a vital feature of towns and cities, yet remarkably little is known or documented about how well they cope with the pressures of the urban environment, how that is changing with a warming climate, and how we can help urban trees survive and adapt to those challenging conditions.

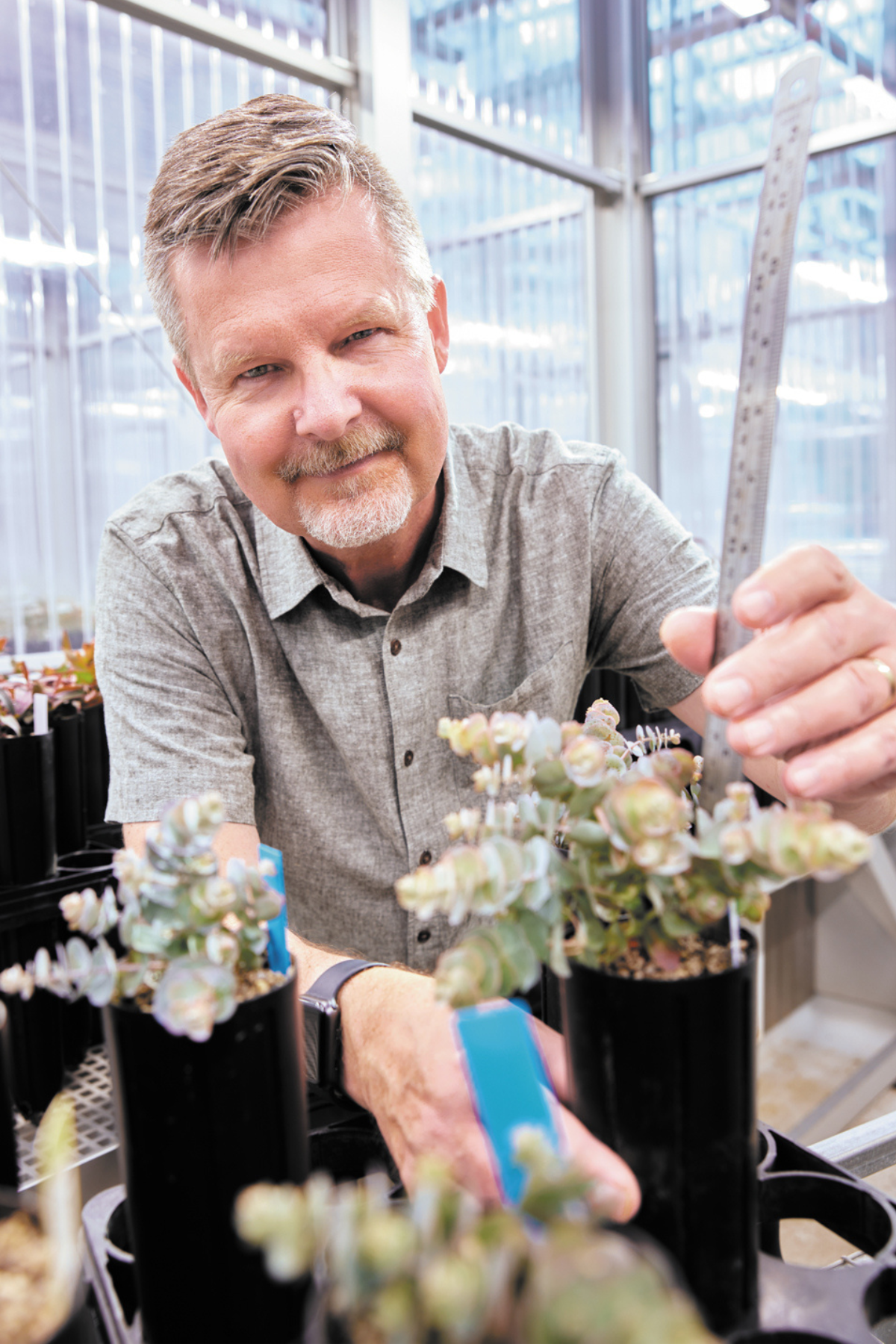

This is where the work of Western Sydney University researchers, Professor Mark Tjoelker and Dr Manuel Esperon-Rodriguez, comes in. At Western’s Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, they have been developing datasets and guidelines that will help secure a greener, healthier and more sustainable urban treescape.

SUPPORTING SAPLINGS

"As a nature-based solution to the urban heat-island effect, trees have an outsized impact in urban environments compared to their role in natural environments," Tjoelker says. Their ability to shade heat-absorbing surfaces can have a big effect on urban energy consumption by reducing air-conditioning needs. "Some studies have shown that trees in urban environments can directly reduce energy consumption by 10 or 15%," he says. "That’s a huge potential contribution to getting to net zero carbon emissions."

To help urban landscapers pick the healthiest, most viable saplings at a plant nursery, Tjoelker and colleagues have developed a new national standard, accredited by Standards Australia: AS 2303:2018 Tree Stock for Landscape Use. These national standards exist to ‘ensure the quality and consistency of products and services, ranging from bushfire-resilient building to designing for access and mobility.

To develop this standard, the research team gathered biometric data on nearly 14,000 container-grown trees in plant nurseries — representing 159 tree species commonly used by urban landscapers across Australia.

"The standard has a checklist of different criteria that are used to help ensure quality," Tjoelker says. "It will help ensure that the tree has every chance, if planted in the correct location and treated right, to survive, grow and thrive."

That checklist includes questions about whether the volume of the pot is suitable for the height and diameter of the tree, and whether the potted roots have the proper form and are free from defects. "It ensures the right balance between the roots that need to supply water and nutrients to the tree and the above ground portion of the tree," Tjoelker says. "If that’s too small, the tree will really struggle to get a foothold in the landscape."

"Purchasers now have a clear standard to quote when purchasing tree stock and the result of this is a high-quality product being supplied that will have a greater survival rate; this means our cities and towns are going to be greener, safer and cooler," says Hamish Mitchell, the managing director of Specialty Trees, one of the nurseries that uses the new standard.

Need to know

- By including trees in urban environments, temperatures can be lowered.

- Researchers from Western’s HIE are helping city planners choose the best trees for their urban forests.

- They have also developed a new national standard for saplings.

PICKING THE RIGHT PLANT

Ensuring that young trees have the best possible chance to flourish is just one part of the challenge; equally important is deciding which tree species to plant in a particular location.

Esperon-Rodriguez has long been fascinated by trees. He began his research career in the mist-cloaked cloud forests of Mexico, studying how tree species in that unique setting are dealing with the changes in climate that are threatening to dry out the lush environment. A post-doctoral opportunity brought him to Australia, and eventually to Western Sydney University and the Which Plant Where research programme: a joint initiative of Western Sydney University, Macquarie University, the NSW Department of Planning and Environment, and Hort Innovation.

The aim of that five-year project was to build a resource for all those involved in developing urban greenscapes to enable climate-ready decision making and to develop resilient green spaces of the future. To do that, the project team has gathered extensive information from around Australia about what factors are associated with urban tree success or failure, with a particular eye on how climate change is shaping these outcomes.

"I spent two years contacting people at the councils of more than 200 cities all across Australia, asking if they could give me any species lists or names that they were no longer planting because of climate change, because they knew they were failing," Esperon-Rodriguez says. It turned out that very few city councils had that data recorded in any systematic fashion, which is perhaps unsurprising given the myriad reasons why any particular urban tree might fail: climate and weather, planting techniques, species vulnerability, damage, vandalism or poisoning.

Esperon-Rodriguez widened his search to a network of people in 14 countries around the world, and still came up empty handed. It showed there was a desperate lack of information, and at a time when it was badly needed. “I decided I wanted to do something about climate change and urban trees and try to help councils to identify the vulnerable and resilient species,” Esperon-Rodriguez says.

That took the form of a comprehensive assessment of the distribution of more than 3,000 urban tree species in 164 cities globally, which expressed that distribution in terms of those species' tolerance for climatic conditions such as temperature and rainfall.

It revealed some surprises, including non-native tree species whose original distribution might suggest they weren’t well suited to Australian temperatures but were in fact thriving, and native species that weren’t coping nearly as well as expected. "The models can say this species is vulnerable, but in reality, we can see that the trees are surviving quite well," Esperon-Rodriguez says.

It’s valuable information for local governments trying to plan for urban treescapes, says Karen Sweeney, an urban forester with the City of Sydney Council. "We want to get 40 to 80 or even 100 years out of some trees, particularly in parks," she says. "In our streets, it’s about making sure that we have good environments and the right adaptive trees to be able to thrive in those harsh environments for the long term."

PICKING THE RIGHT PLANT

The research group is also looking into the past to see how existing trees have coped with previous climatic variation. Esperon-Rodriguez is studying tree cores taken from trees in Adelaide, Mandurah, Melbourne, Mildura, Parramatta, Penrith, and Sydney, to record how tree growth has changed over the life of that tree. Again, this has revealed some surprises.

"We thought that the trees in hotter, drier Mildura were going to have lower growth compared to Sydney or Melbourne, for example." But it turns out they’re doing just as well, suggesting some trees are able to adapt to local climates. Esperon-Rodriguez is now looking more deeply into this, examining how some species of trees vary in their morphology across different climates, such as producing smaller leaves to reduce water loss.

The work being done at Western complements the existing expertise of urban foresters like Phillip Julian, who works with the City of Sydney Council. They have a tough job, because urban environments are becoming ever more crowded. "Competition for space is increasingly becoming important, so we need to coordinate our tree planting activities with other activities in Council," Julian says.

Tree species are selected for the space they will occupy above and below ground, the conditions of the location now, and how they look and behave through different seasons, "but the missing part of that puzzle was we don’t have a crystal ball to look to the future and see how that species is going to do in 20, 30, 50 years’ time," Julian says. "Manuel has helped to fill that gap and give us some confidence and an evidence-based grounding about what we think might do well into the future."

Meet the Academic | Professor Mark Tjoelker

Mark Tjoelker is associate director of the Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment and a research leader in sustainable ecosystems and climate change.

Professor Tjoelker is a leading expert in plant biology and ecology whose research spans forestry, horticulture, and agricultural systems. He is perhaps best known for his work on climate change impacts on respiration and carbon cycling, climatic adaptation in plant traits and the biogeography of forest trees. He has authored over 170 scientific journal articles and is among the top 1% of the most highly cited scientists worldwide (Clarivate Analytics).

The goal of his research is to advance fundamental knowledge of plant and ecosystem responses to environmental change and provide science-based knowledge to inform policy choices.

Professor Tjoelker’s research promotes urban forests as a nature-based solution for mitigating climate change impacts. His research catalysed the adoption of a new national standard, Tree Stock for Landscape Use (AS 2303:2018) that has changed grower practices and is driving consumer confidence while broadening public support for urban greening initiatives. This work won the 2019 Award of Merit from the Australian Institute of Horticulture.

His appointments include the Australian Academy of Sciences Roundtable on novel negative emissions approaches for Australia (2022), the Australian Research Council College of Experts (2019 to 2021), Forestry Research Advisory Council to the US Secretary of Agriculture (2010 to 2011), and Fulbright Scholar (1995).

Professor Tjoelker holds a BSc in biology from Calvin University (USA), an MSc in botany from the University of Tennessee and a PhD in forestry from the University of Minnesota. Prior to arriving at Western in 2011, he held an academic position at Texas A&M University, USA.

Meet the Academic | Dr Manuel Esperon- Rodriguez

Manuel Esperon-Rodriguez is a Research Theme Fellow, Environment & Sustainability and an ecologist who studies the effects of climate on plant function. Manuel has expertise in spatial analysis and modelling, particularly the novel use of ‘big data’ approaches to address questions related climate change impacts on urban ecosystems. His research incorporates climate adaptation into management and conservation of urban environments and combines modelling approaches with new empirical data to identify resilient and vulnerable species in the context of future climates, across global cities. Manuel’s research also focuses on the health and wellbeing, physical and social determinants that make up sustainable urban environments, which aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, specifically for sustainable cities.

Credit

Future-Makers is published for Western Sydney University by Nature Research Custom Media, part of Springer Nature.