You can search for courses, events, people, and anything else.

Separated by more than 7,400 kilometres stand two buildings: 82 Harbour Street in Sydney, Australia, and 86 Yuelai Road in Zhongshan, China. Behind each of their modest facades lies a rich shared history, one that connects generations of Chinese Australians to both countries.

"While Australia has lots of buildings that date back more than 120 years or so, it also has a built heritage overseas. China’s heritage also transcends national boundaries," says Professor Denis Byrne, who leads the China-Australia Heritage Corridor project with Distinguished Professor Ien Ang.

Supported by an Australian Research Council grant, Byrne and Ang have been investigating the post-1840s bidirectional flow of people between Australia and China, captured in both physical places and family histories. It is in this context that they have been documenting the history of the two grocery stores. The findings of their wider research have been shared in a public database, which is helping many Chinese Australians trace their roots and deepen their sense of identity.

FROM SYDNEY AND SHEKKI

Both Harbour Street and Yuelai Road were sites for grocery stores owned by Chee Win Lee. Born in Zhongshan, Lee immigrated to Australia in 1900 and soon opened a grocery shop at 82 Harbour Street which he named Yet Shing & Co. Ten years later, having saved enough money, Lee returned to Zhongshan and married. He opened a second grocery shop at 86 Yuelai Road in Shekki, Zhongshan’s main commercial hub, and built a house nearby on Meiji Street for his wife and children. Lee himself, however, returned to Sydney and regularly sent money home.

"As so often happens with migrants, they often intend to go back to their home country but develop ties to the places they migrate to. This could be in the form of a business or a marriage," says Byrne. "Essentially, they set down roots."

Lee’s living arrangements were typical for many migrants to Australia at the turn of the century. Decades after a gold rush which brought many Chinese migrants into the country, Australia introduced the Immigration Restriction Act in 1901, designed to restrict non-European migration and make it difficult for the Chinese men working in Australia to bring their families with them.

Eventually, however, Lee was able to bring his family to Australia. The first to arrive was his son, Wah Hook, who arrived in 1923 aged 12-years. In 1938, as the Japanese invaded China, Lee returned to Shekki to bring the rest of his family out of China.

Need to know

- The Chinese-Australia Heritage Corridor examines the bidirectional flow of people between the two countries.

- The research highlights the strong transnational connection between Australia and China.

"The research highlights the continuing strong transnational connection between Australia and China."

MARKET GARDENERS

Lee’s son, Wah Hook, later married Doris Gay, whose mother had a Chinese father and an English mother. The Gay family traces their time in Australia back to Louis Gay, who was born in Zhongshan and came to Australia at age 17. After a stint managing a banana plantation in Fiji, Gay struck out on his own as a market gardener in Sydney, first on leased land at Rose Bay and then on land he bought at Guildford.

Farming saw the Gay family through up to the 1950s, when the land was acquired by the government. The family grew lettuce, potatoes and other vegetables, taking their produce to a stall in Sydney’s Haymarket by horse and cart, and later by truck. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the farm provided the family with a stable source of food, and when World War II broke out, the sons were spared military service since market gardening was seen as an essential industry.

Farmers like the Gays brought Chinese agricultural techniques refined over hundreds of years to Australia, including methods of irrigating the often-dry soil. "In addition, there were plant seeds flowing in from China, as well as a whole range of commodities such as dried seafood and other preserved goods," says Byrne.

"On the one hand you had remittances being sent back from Australia, so there’s a flow of money in that direction being used to build houses and so on," Byrne continues. "Flowing in the opposite direction, you had knowledge and ideas about farming."

RETURN TO YUELAI

After their wedding in the early 1930s, Wah Hook and Doris lived in Shekki for a year, staying in the Meiji Street home built by Chee Win Lee. Upon their return to Sydney, they first stayed at the Gay market garden where their son William was born in 1934, subsequently moving to a house close to the grocery store on Harbour Street in Haymarket.

Unlike his father and grandfathers before him, William grew up entirely in Australia, studying at Ultimo Primary School and Fort Street High School before attending medical school at Sydney University. He nonetheless remained interested in his heritage, and in 1985 made his first visit to China.

By then, his ancestral home had been destroyed. The grocery store at Yuelai Road, however, was still standing and is today a takeaway food store. Similarly, although the store at Harbour Street closed down in the 1960s, the building remains, and the unit is now a Korean restaurant.

Many members of the Chinese community in Sydney have been able to track down the villages from which their forebears came, visit the ancestral halls there and even have their own names added to the genealogy book, as well as locating the houses built with money sent from Australia. Hundreds of these houses have been listed as heritage properties by the local authorities in China.

"During the 1940s up until the 1980s it wasn’t possible for many of them to go back. Once it became possible, hundreds of them returned to visit, many for the first time," Byrne explains. "The number of houses and the scale of transnational connections between Australia and China had not received much attention before our research."

THE NEW WAVE

Today, William lives in Parramatta with his wife, Nancy. Both were interviewed for the China-Australia Heritage Corridor project in 2017. With four generations of memories, the Lees are firmly woven into the fabric of the local community. Recent years have seen a new wave of immigration bringing large numbers of Chinese and Indian migrants into the area.

"In a related project, partly funded by the New South Wales Government’s Heritage Office, we are looking at the way the new wave of immigrants are making their own heritage in the area," says Byrne. "We are asking them how they relate to Indigenous heritage and old buildings in Parramatta, including heritage sites of the colonial era. It’s been really interesting to see how they’ve been building connections and developing their own perspective."

By tracing the unusual connections between seemingly ordinary places and everyday people, this research has not only deepened the identities of individual participants, but also raised awareness of the Chinese Australian community’s shared history. "The research also highlights the continuing strong transnational connection between Australia and China which these migrants and their descendants have maintained. This is especially important today as a counter against challenges in the political relationship between the two countries," adds Ang.

Meet the Academic | Distinguished Professor Ien Ang

Distinguished Professor Ien Ang is a global leader in cultural studies and a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities. Her wide-ranging scholarship has focused on media and popular culture, cultural globalisation, migration, multiculturalism and transnationalism, with a special interest in Asia-Australia relations, Chinese diasporas, and the role of cultural institutions in representing and nurturing diversity. She joined Western Sydney University in 1996 and was the Founding Director of the Institute for Culture and Society. Her books include Watching Dallas: Sopa Opera and the Melodramatic Imagination, Desperately Seeking the Audience, On Not Speaking Chinese: Living between Asia and the West, Chinatown Unbound: Trans-Asian Urbanism in the Age of China, and most recently, The China-Australia Migration Corridor: History and Heritage (edited with Denis Byrne and Phillip Mar. She has collaborated with a range of organisations including the Special Broadcasting Service (SBS), the City of Sydney, the Australia Council, and the Powerhouse Museum.

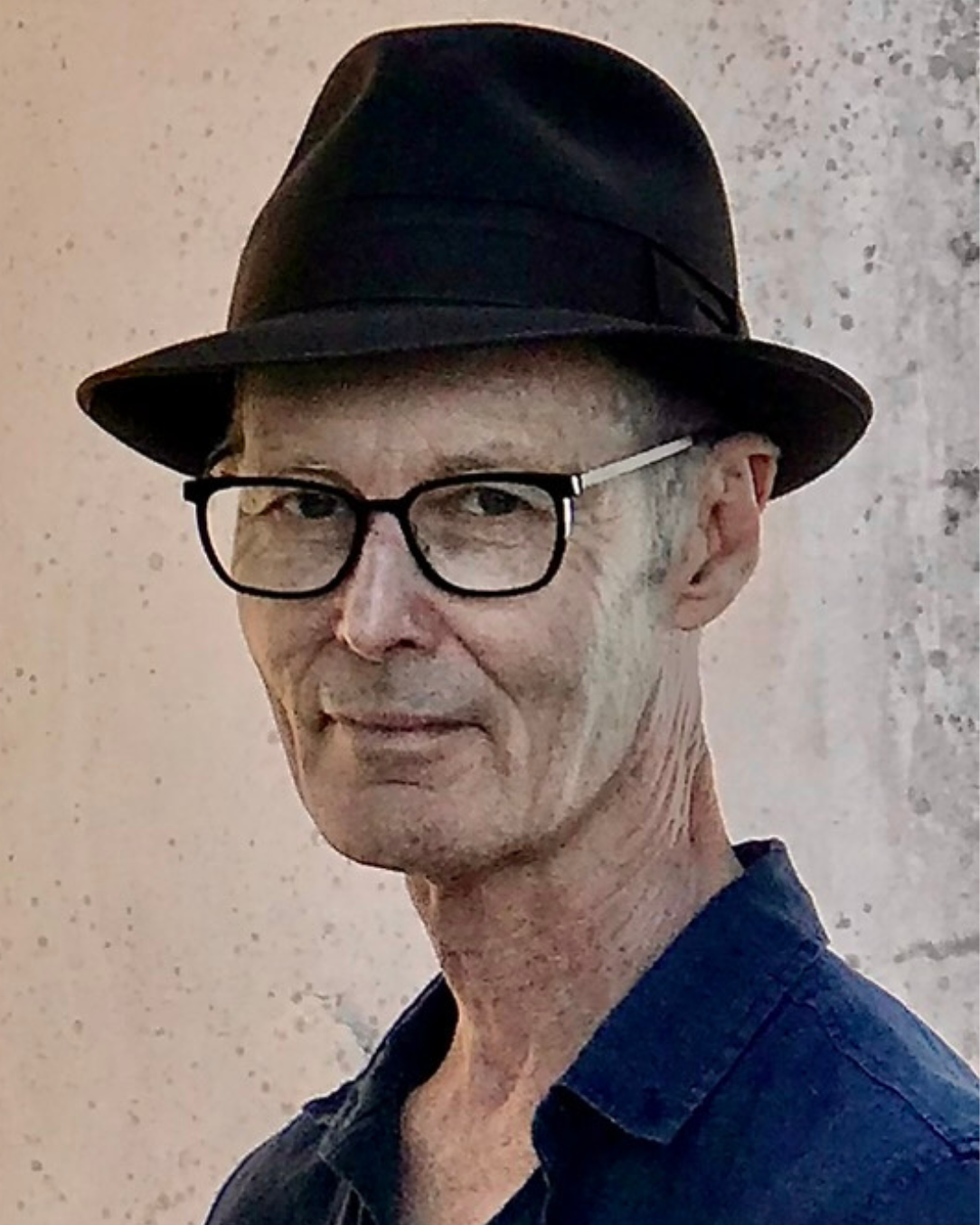

Meet the Academic | Professor Denis Byrne

Denis Byrne is a Professor of archaeology and heritage studies at the Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University, and a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities. With a focus on Asia and Australia, he works across the fields of the archaeology of the contemporary past, critical heritage studies, and the environmental humanities. For several years he has been researching the material heritage of Australia’s history of immigration. Focusing on Chinese migration to Australia between the 1840s and 1940s, he proposes we adopt a ‘heritage corridor’ approach that recognises the enduring ties that many or most migrants have to their ‘home’ countries and that we thus think of their heritage in transnational terms. His research on the transnationally distributed heritage of Chinese migration to Australia is published in The Heritage Corridor: A Transnational Approach to the Heritage of Chinese Migration (Routledge 2022) and in his 2023 article, 'The migration heritage corridor: transnationalism, modernity and race.' His books Surface Collection (Rowman & Littlefield 2007) and Counterheritage: Critical Approaches on Heritage Conservation in Asia (Routledge 2014) explore new approaches to the writing of archaeology and heritage and challenge heritage practices in Asia that seek to secularise sites of popular religion.

Credit

Future-Makers is published for Western Sydney University by Nature Research Custom Media, part of Springer Nature.

© Markus Spiske/Pexels

© Ian Turnell/Pexels

© Michael Burrows/Pexels

© aiyoshi597/Shutterstock