You can search for courses, events, people, and anything else.

“Bats are really hard to study,” says Associate Professor Christopher Turbill from Western Sydney University’s School of Science. They are active at night, they move around a lot, and they’re often very small. All of which makes being a bat researcher a tough gig.

“You’re peering into the dark. Bats are very difficult to even see, let alone get an understanding of what they’re up to,” he adds. Yet a better understanding of bats is key to resolving bat-human conflicts emerging all over Australia, and protecting them against growing threats, including a deadly fungus.

To fill knowledge gaps, Western’s BatsLab — led by Turbill and Professor Justin Welbergen, of Western’s Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment — is turning to new technology.

More than 80 species of bat are found in Australia. They range in size from a few grams up to a kilogram, and each has its own ecological niche. Bats pollinate crops, they control insects that are agricultural pests or carry disease, they disperse native seed, and energy from their faeces can support unique cave ecosystems.

But beyond bats having ‘useful’ roles in ecosystems, Welbergen adds that “we should also value them purely for their own sake, like we do more visible animals.”

TURBINE TROUBLES

But not all Australians appreciate bats. Fruit- and nectar-eating flying foxes, which make a lot of noise and mess, can provoke the ire of some people.

For example, in 2016, around one quarter of Australia’s population of grey-headed flying foxes — some 300,000 bats — descended on Batemans Bay, New South Wales, to feast on flowering gum trees.

“I can’t open my window at all because the smell is so bad,” one local complained to the Associated Press, prompting the local authorities to attempt to disperse the bats with loud noise and smoke, much to the consternation of researchers and other wildlife conservationists. Moreover, flying foxes are also in the firing line of farmers, who report fruit harvests being stripped.

And the latest concern for Welbergen and Turbill is the growth of wind power in Australia, with bats being increasingly hit by wind turbine blades. It’s a complex problem though, says Welbergen, as “we need development of wind farms, to mitigate climate change, and one of the major threats to bats, especially flying foxes, is climate change.”

Minimising the impact of bats on humans, and vice versa, requires better understanding of Australian bats more generally, so Turbill and Welbergen are deploying emerging technology to help them achieve this. Included in their toolkit are heat-sensing drones, ultrasonic bat detectors, temperature-sensitive radio transmitters and data from the Bureau of Meteorology’s (BOM) rain radar.

Appropriately for studying bats, the BOM rain radar works a little like bat sonar, but instead of bat-squeaks, a ground-based transmitter sends out pulses of radio waves into the sky. This bounces off moisture in the atmosphere, giving a reading of rainfall levels.

Because bats are full of moisture, the BatsLab team can use the BOM data to extract information about numbers of flying foxes departing their roosts at sunset. They have coupled this with more fine-grained data from their own heat-sensing drones to improve the estimates. While radar has been used overseas to study smaller bats, Welbergen says they are the first to attempt this for flying foxes.

The team has shown that up to one fifth of the individuals in a flying fox colony turns over every night, with some bats moving on to greener pastures, and others arriving from elsewhere. This suggests that dispersal strategies like the ones used in Batemans Bay are likely to be only partially effective, as new bats arrive every day. The bats probably departed on their own because they are nomadic, Welbergen says.

TINY HEAT DETECTORS

Among other technology that BatsLab researchers are using are temperature-sensitive radio transmitters. Flying foxes are famously susceptible to heat waves, with a joint project between Western and the NSW Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water reporting the largest loss of flying foxes to extreme heat in a single summer in 2019–2020.

Matthew Mo from the Department says the project “created broader awareness of extreme heat as an emerging threat,” and was referenced by an international initiative to review the conservation status of the grey-headed flying fox in 2021.

But according to Welbergen, the heat-stressed fruit bats are perhaps just the most visible victims of climate change. Bats and indeed other mammals that live solitary lives in the forest may be just as susceptible, but don’t so obviously die in dramatic numbers.

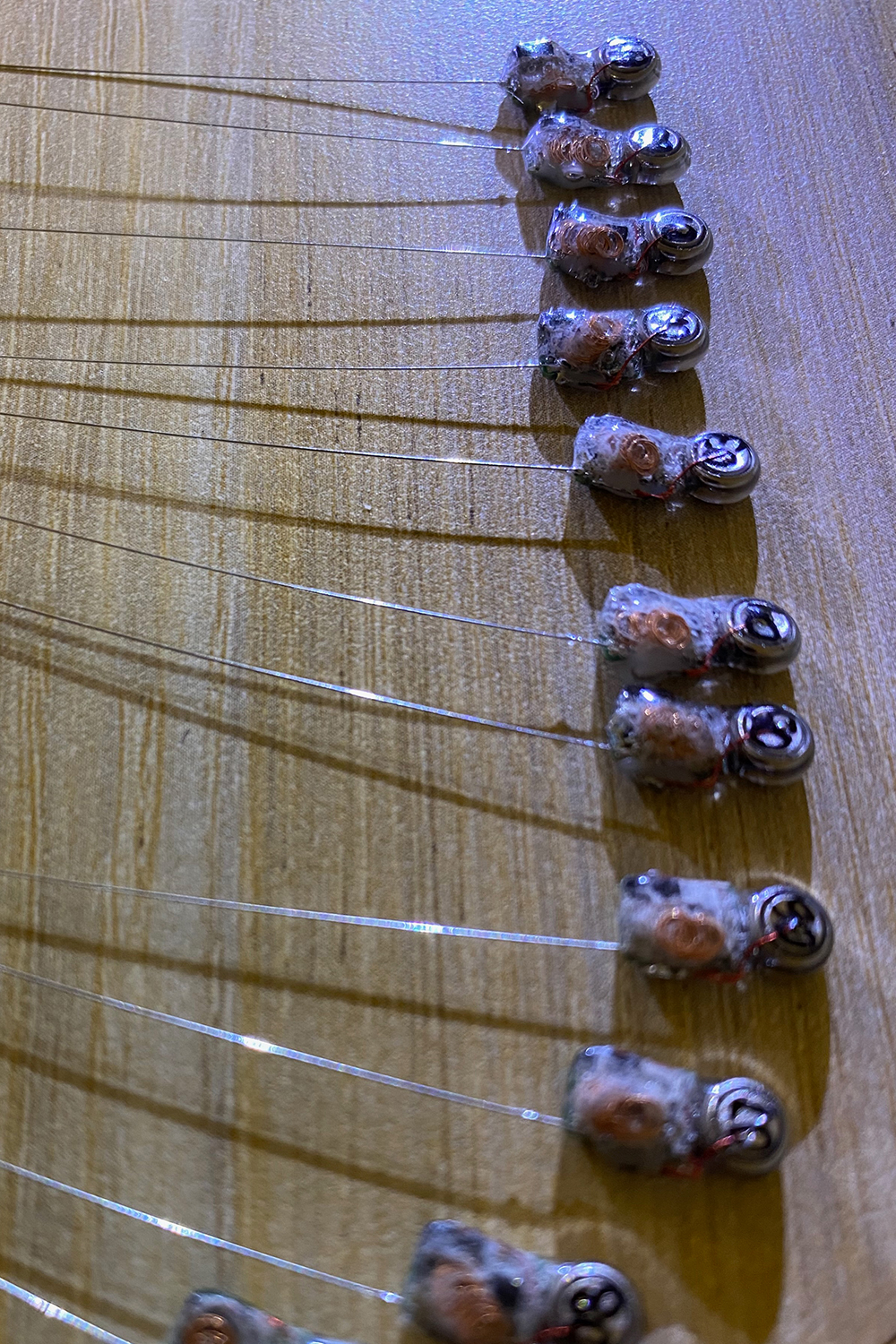

The team are trying out tiny, implanted heat detecting transmitters, so their temperatures can be monitored in the wild. These transmit data, which can be picked up by strategically placed data-loggers.

While this technology will be useful to understand bats’ response to extreme heat, Welbergen and Turbill are also keen to understand what bats do when they are cold. This information is key to figuring out how vulnerable Australian bats are to a fungus that has almost wiped out many North American species.

DEATH BY FUNGUS

Pseudogymnoascus destructans causes ‘white nose syndrome’, where hibernating bats’ skin becomes mouldy, leading to wing damage and emergance from hibernation too early. Mortality rates can be as high as 90 to 100%. Nine years ago scientists predicted this fungal pathogen was “almost certain” to arrive in Australia within the next ten years. So Turbill and Welbergen have spent much of the past few years scrambling to better understand Australian bats’ sensitivity to the disease.

In North America, the bats had little immunity to the fungus, which likely came from Asia or Europe. American bats, which endure a harsher winter than Australian bats, hibernate, which involves dropping their body temperature. This creates more favourable conditions for the cold-loving fungus to thrive.

BatsLab’s work with temperature-sensitive radio transmitters has shown that some southern Australian bats also hibernate in caves during winter, dropping their body temperature to the range preferred by the fungus.

“This research project, led by Western Sydney University, is so important,” says Keren Cox-Witton, from Wildlife Health Australia, who works with BatsLab. She says white nose syndrome presents “a real risk to a number of our hibernating, cave-dwelling bats, including the critically endangered southern bent-wing bat.”

BatsLab’s work has helped to identify the species and caves most at risk from white nose syndrome so that protective and preventative measures can be put in place before the fungus, inevitably, arrives.

This is in line with the BatsLab team’s wider mission: to employ cutting edge technology, combined with ecophysiology, behavioural ecology and conservation research, to better understand the drivers of bat declines in Australia and provide the robust scientific evidence needed to underpin appropriate management interventions.

Need to know

- Researchers from Western are using heat-sensing drones, temperature-sensitive radio transmitters and rain radar data to study flyingfoxes.

- This will help us understand bats’ response to climate change.

Meet the Academic | Associate Professor Christopher Turbill

Christopher Turbill is an Associate Professor in the field of animal physiological ecology at the School of Science, and a School-based researcher in the Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, Western Sydney University. Prior to his Lectureship, Christopher conducted postdoctoral research fellowships awarded by the Austrian Science Fund and the Australian Research Council (DECRA) and gained his PhD from the University of New England. He has also been employed outside of academia as a field ecologist. Christopher’s research combines thermal and metabolic physiology with behavioural ecology to answer fundamental and applied questions about how animals interact with their environment. His work has made important contributions to understanding the ecological consequences of controlled variation in body temperature by mammals and birds and its links with metabolic energy expenditure, activity and the evolution of different life-history strategies. Christopher's research also seeks to understand and resolve conflicts between human-related environmental change and the ecological requirements of animals and the conservation of their populations.

Meet the Academic | Professor Justin Welbergen

Credit

Future-Makers is published for Western Sydney University by Nature Custom Media, part of Springer Nature.

© Tracielouise/E+/Getty