You can search for courses, events, people, and anything else.

The waste flushed down the toilet is of no consequence to most of us as we leave the bathroom. But for Professor Jeff Powell and Dr Jason Reynolds, researchers at Western Sydney University, that rush of water in the toilet bowl hints at the possibility of a fertile supply chain — one that passes through wastewater treatment plants and into fields, gardens, and greenhouses.

The pair are laser focused on urine-based fertilisers as part of the Australian Research Council Research Hub for Nutrients in a Circular Economy (NiCE Hub), an ambitious A$2-million effort to recover useful nutrients from the wastewater stream. The Hub is a collaboration between universities and utility providers, and includes engineers, soil scientists, microbiologists and policy thinkers, all working to transform urine into a safe, effective fertiliser.

The idea isn’t new — civilisations have recycled human waste for millennia. “But now we’re trying to make it safe, scalable and acceptable,” explains Reynolds, a soil scientist at Western’s School of Science.

At the core of the project are two products: UrVAL and UGold. Developed by teams at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and the University of Melbourne, these are different urine-derived fertiliser systems. Both begin with source-separated urine, but UrVAL relies on membrane bioreactors to sanitise and concentrate nutrients, while UGold uses electrochemical processes with ion-exchange membranes to recover and concentrate nutrients. The result is a stable fertiliser product with minimal odour and low pathogen levels — typically yielding one litre of liquid fertiliser from every ten litres of urine.

The liquid is rich in nitrogen, phosphorus and trace elements, exactly what plants need to grow. However, “just because you can extract nutrients doesn’t mean you know how they’ll behave in soil,” says Powell, an expert on soil microbiomes at Western’s Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment. That’s where Western Sydney University comes in. While engineers focus on extraction, Powell and Reynolds are testing how these products interact with ecosystems. In greenhouses on the Hawkesbury campus, one of their PhD candidates, Niraj Yadav, runs trials with model grasses, adjusting dosage rates and pH levels. Too much, and the salts or pH in the fertiliser could damage the soil, explains Reynolds.

SECURING SOILS

The early results are promising. In some trials, plants fertilised at Western with UrVAL have outperformed those given conventional nitrogen fertilisers. But the team is cautious. They’re still learning how these products affect long-term soil health, says Powell. That includes monitoring changes in microbial communities and carbon retention.

UrVAL, for example, is acidic, which can suppress certain microbial processes (such as nitrification) and select for acidophiles, microorganisms that thrive in acidic conditions. It also contains dissolved salts, which at high levels may cause salinity stress or nutrient imbalances, particularly in sandy soils with low nutrient-holding capacity, like those common in Sydney’s west. There is a further risk of sodicity, which can damage soil structure and reduce long-term fertility due to excess sodium levels.

That’s why the researchers are now mixing UrVAL with ‘biosolids’, another product of wastewater treatment. These compost-like materials are derived from heat treating the sludge remains after wastewater has been separated, treated, and discharged to the environment.

“In testing, we’re seeing signs that this combination is raising soil pH,” explains Reynolds. “It appears the biosolid is acting as a buffer, helping to neutralise the acidity of the UrVAL. The biosolid substrate may contribute to this effect, reducing the net acid load delivered to the soil.

Biosolids are rich in organic matter, and when they are applied to land they help restore the soil’s ability to hold water and provide nutrients, says Lyndall Pickering, a program manager at Sydney Water, a key industry partner of NiCE Hub. Sydney Water treats wastewater from nearly 5 million people in Greater Sydney and recovers biosolids during the treatment process. Rather than send biosolids to landfill, Sydney Water has been delivering all of its biosolids — roughly 40,000 dry tonnes a year — to farmers, compost producers and forestry since the 1990s.

The UrVAL-biosolid mix is now being tested on wheat- and legume-like model plants at Western, while a team at the University of Southern Queensland, in Toowoomba, is testing a mix of UGold and biochar (a charcoal product also derived from biosolids) on crops. The two teams work closely together, testing their different plants and soils in parallel.

STEADY SUPPLY

The nitrogen-rich system makes sense from a resource perspective. “Australian farms have a huge demand for nitrogen-based fertilisers,” notes Reynolds. “And the standard Haber-Bosch approach is expensive and energy-intensive to produce.”

Unsurprisingly, Australia is not the only country testing this idea. Swiss researchers are pioneering urine purification technologies and American research teams are trialling direct urine application.

But Australia, Reynolds argues, is ahead of the curve when it comes to integration of products and rolling these new products out to broadscale agricultural trials. “The ARC NiCE Hub has developed a membrane system that’s not only effective but scalable,” he says. “That’s the hurdle most others haven’t cleared.” Pilot plants in Sydney are already producing UrVAL at scale, and the team is now presenting the technology to international industry partners.

Still, the project’s success depends on more than just science. “It requires regulatory approval and public trust,” says Powell. But the very real hope is that wastewater treatment plants will evolve into complex, responsive hubs “not just for sanitation, but for significant resource recovery,” adds Reynolds.

Meet the Academic | Professor Jeff Powell

Professor Jeff Powell obtained his PhD from the University of Guelph, Canada in 2008, where he studied the biological impacts of genetically modified crops on soils, including mycorrhizas, rhizobia, and soil fauna.

His postdoctoral research at the Freie Universität Berlin, Germany, examined the role of fungal traits in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis and factors controlling the predictability of microbial community assembly, both of which have relevance for the management of microbial communities and their ecosystem services.

He joined the Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment in 2011.

Professor Powell is interested in the processes underlying the assembly of microbial communities and how these processes can be manipulated to achieve beneficial outcomes. A goal of his research is to understand the contributions of microbial biodiversity to the productivity of managed and natural systems and to how these systems respond to environmental change.

Outcomes of this work will be a greater understanding of i) how mycorrhizal fungi, rhizobia, and other microbial associates of plants control aspects of carbon and nutrient cycling and ii) how these can be managed to confer greater benefits to plants (linked to enhanced nutrient uptake and reduced impacts of pathogens).

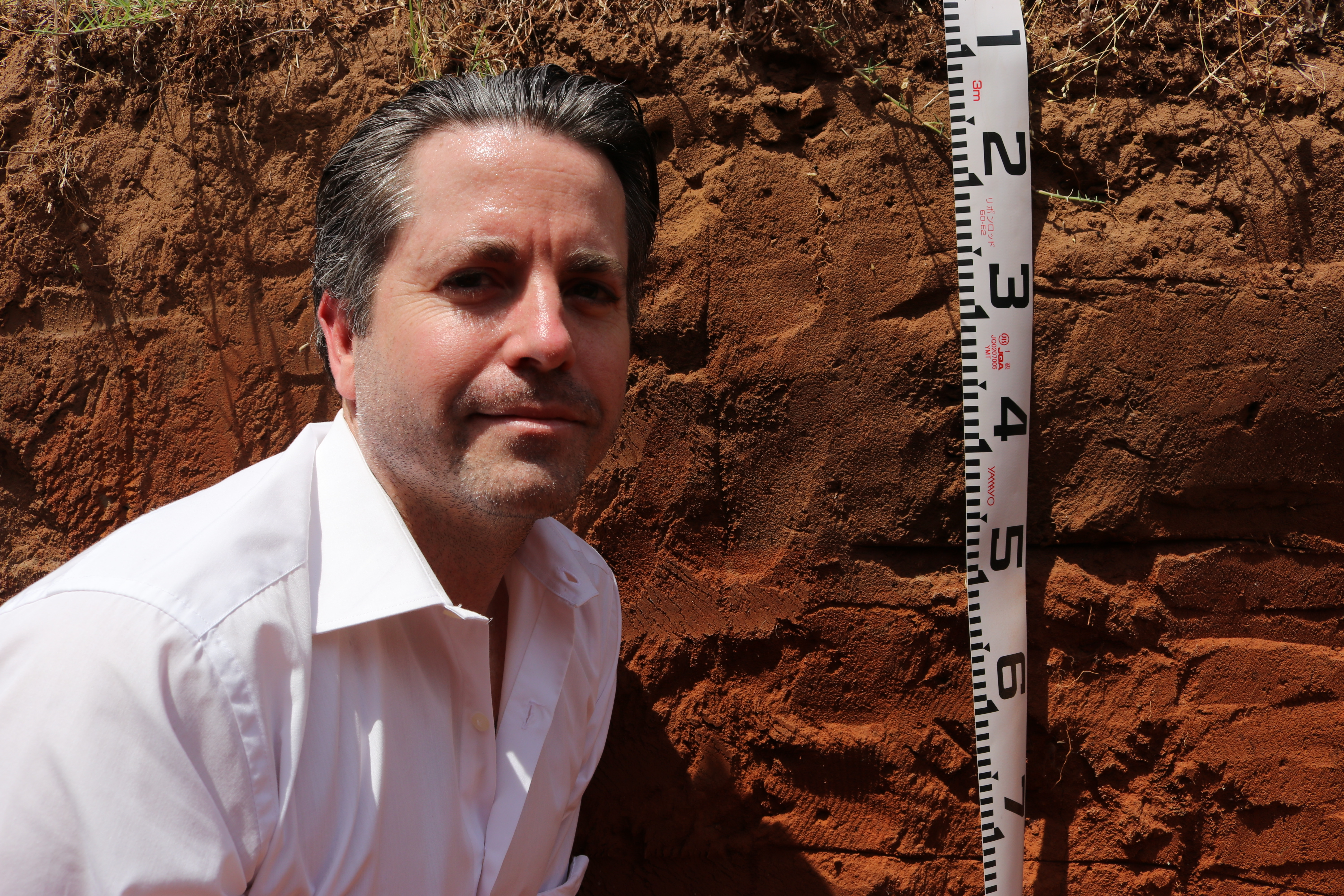

Meet the Academic | Dr Jason Reynolds

Dr Jason Reynolds is a soil scientist and Senior Lecturer in the School of Science at Western Sydney University, where he teaches into the Environmental Science and Agriculture programs. He has served as Scholar-in-Residence at the Powerhouse Museum and is a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy.

His research focuses on peatlands and acid sulfate soils, exploring their evolution and role as markers of the Anthropocene epoch. He is also a Chief Investigator in the ARC Research Hub for Nutrients in a Circular Economy (NiCE), contributing soil expertise to a national research network that aims to recover and recycle nutrients from urban, agricultural, and waste streams, helping to close nutrient loops and promote circular-economy practices.

He is President of the NSW Branch of Soil Science Australia and a board member on the organisation’s Federal Accreditation Board. Through these roles he contributes to SSA’s mission of advancing soil science, maintaining professional standards, and promoting the responsible management of Australia’s soil resources.

Credit

Future-Makers is published for Western Sydney University by Nature Custom Media, part of Springer Nature.

© Quantic69/iStock/Getty

Image source: Pexels.com