You can search for courses, events, people, and anything else.

Delayed flights don’t typically breed innovation. But for Professor Anand Hardikar, a weather-related travel delay in 2009 gave him six hours for some unscheduled blue-sky thinking. This ultimately led to a dynamic risk score for both predicting the onset of type 1 diabetes and gauging an individual’s response to cell therapy and drug therapy for the disease.

Hardikar, a biologist at Western Sydney University’s School of Medicine and Translational Health Research Institute, was flying from Mumbai to Melbourne that day with the School of Medicine’s Associate Professor Mugdha Joglekar, his partner in life and research. “We work much better together,” he says. “Our children almost began to hate research careers, because it took up most of the dinner-table conversation.”

One of the major challenges in diabetes research is that only 20% of individuals who develop type 1 diabetes have a family history of the disease. “And that’s really mind-boggling, because it means that anyone from the general population can be at risk of the disease, not only those who have a genetic predisposition to the condition,” Hardikar explains.

When someone without diabetes eats, carbohydrates in their food are converted into glucose, which enters the bloodstream and raises the blood sugar level. This triggers the release of insulin, which moves through the blood, helping cells to absorb the glucose and reducing blood sugar levels again.

In people with type 1 diabetes, the cells in the pancreas that produce insulin have been destroyed by the immune system, reducing and eventually halting insulin production. This immune destruction is easy to spot in mouse models, but in humans, the immune attack on insulin-producing cells is milder, occurs more slowly, and varies across ethnically diverse individuals.

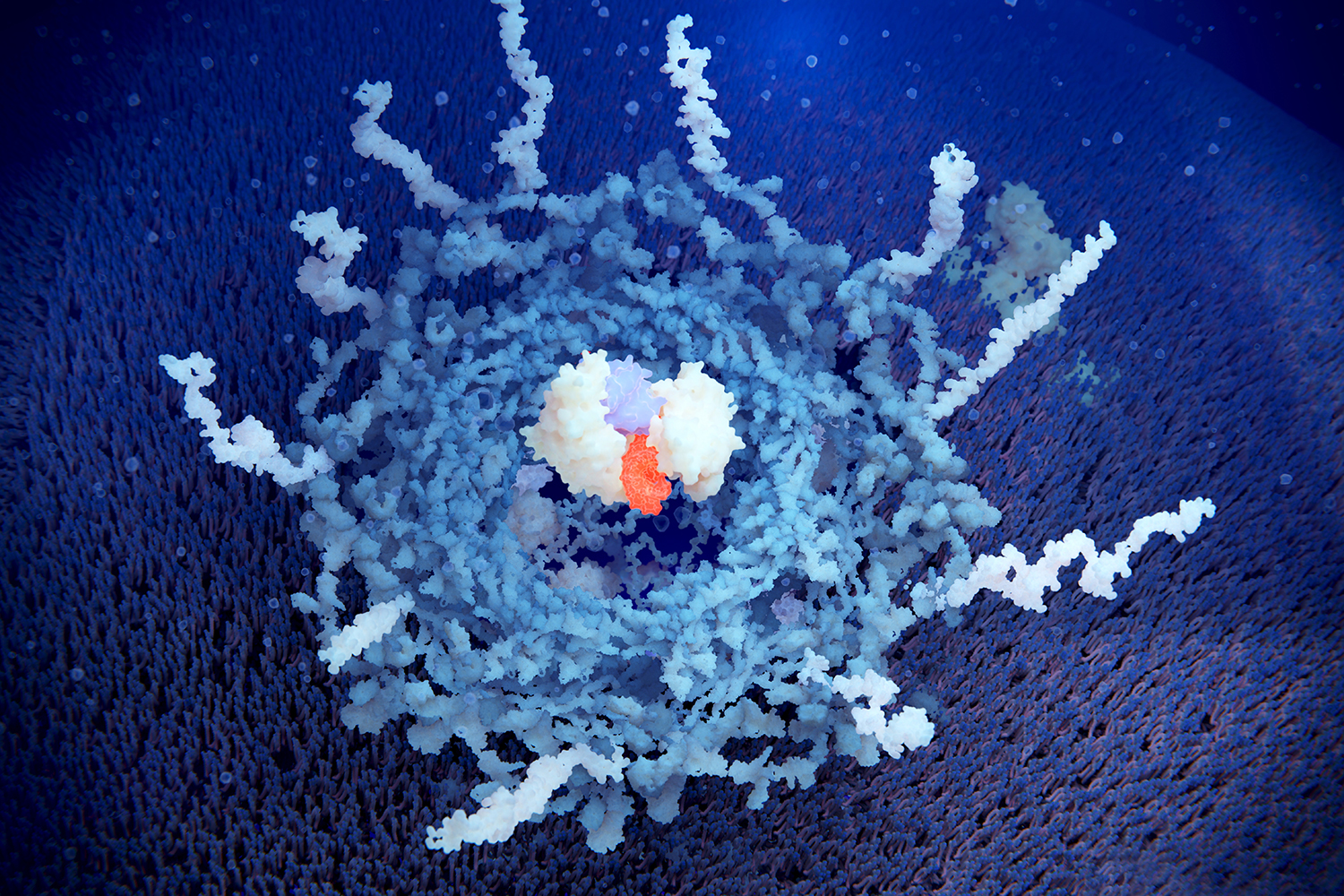

In 2009, Hardikar and Joglekar had been researching diabetes for some time, but they had only just started working on microRNAs — tiny non-coding RNA molecules that regulate protein production. They had recently discovered how microRNAs regulate the genes involved in development of the pancreas, and they thought they might be able to map that knowledge to type 1 diabetes.

The back of a boarding pass became a blueprint for an idea that was 15 years in the making: a way of using microRNAs to diagnose type 1 diabetes. “We thought of the possibility to not just identify and validate these key microRNAs associated with type 1 diabetes, but to tie them into a single score that clinicians could use to stratify type 1 diabetes risk”.

SHIFTING RISK

MicroRNAs turned out to be an excellent biomarker for type 1 diabetes risk prediction because they are remarkably robust; they do not degrade easily (like some other biomarkers) and can be reliably measured in human pancreas tissues or plasma samples.

In 2012, the Australian Research Council (ARC) funded a Future Fellowship proposal for the basic science part of the project, but Hardikar found it difficult to attract more funding because a test for type 1 diabetes was deemed to be of little value without a viable cure at that time.

Research in diabetes therapies quickly caught up. There are now several drugs that have progressed through clinical trials, and one already approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration that delays progression of the disease. For each of these drugs, there will be some people who respond well to the treatment, and others who do not respond at all. Hardikar and Joglekar’s study found that their microRNA measure could predict how individuals would respond in the clinical trial of a drug called Imatinib.

The advent of effective type 1 diabetes drugs introduced another element: dynamic risk. Genetic risk was one of the first measures developed to test for diabetes, but it is highly variable; one of the best-known alleles, or gene variations, associated with type 1 diabetes is present in only 30% of people with the disease. And as Hardikar explains, “Now you have drugs that can change the course of type 1 diabetes, does a high (genetic) risk mean that you would have very low (or no) chance of a cure? Current and emerging drugs are going to change diabetes progression.” This realisation led Hardikar and Joglekar to incorporate dynamism into their risk score.

NEXT STEPS

The next plan is to further improve the accuracy of this risk score by adding other biomarker categories, such as proteins, lipids, metabolites, and cell-free DNA, in these populations of patients used to calculate the dynamic risk score. The microRNA-based model is based on patient data from seven different countries, which were largely contributed by Hardikar’s network of collaborators. With industry support, Hardikar and Joglekar are now also setting up a platform to translate this research-based workflow into a system for patient diagnostics reporting that is compliant with U.S. Food and Drug Administration regulations.

Hardikar is keen to update the training set to include a wider range of patient data from different demographic groups. A second goal is to make it even more accurate by incorporating different machine learning and synthetic data-based analytical workflows.

Professor Flemming Pociot, at the Steno Diabetes Center Copenhagen in Denmark, agrees that the approach has tremendous potential. Pociot is one of Hardikar’s many long-term collaborators.

“The dynamic risk score has clear applications in personalised care,” he says. Integration with other signatures, such as circulating proteins and lipids, will further enhance the accuracy of this microRNA-based risk score.

Hardikar is particularly eager to move in the direction of personalised medicine. “We can now say that a given drug would not be very useful to a particular individual before they start the medication,” says Hardikar, “and that opens up a lot of possibilities”.

Need to know

- Type 1 diabetes is a condition in which the body attacks its own insulin-producing cells.

- It is difficult to predict the changing risk of type 1 diabetes in humans, and a person’s risk of

developing the disease changes over time, based on their environment. - A new dynamic risk measure can predict whether a person has type 1 diabetes, and how they will respond to cell therapy and drugs designed to treat it.

Meet the Academic | Professor Anand Hardikar

Meet the Academic | Dr Mugdha Joglekar

Credit

Future-Makers is published for Western Sydney University by Nature Custom Media, part of Springer Nature.

©Juan Gaertner/Science Photo Library/Getty