You can search for courses, events, people, and anything else.

In the early 2000s, Adam Possamai was a young PhD student studying new age spiritualities at Melbourne’s La Trobe University. At that time, for followers of these belief systems, “religion was no longer about going to a congregation and listening to what a priest had to say,” he reflects. “Instead, religion had become more individualised, with people thinking about religion for themselves, by themselves.”

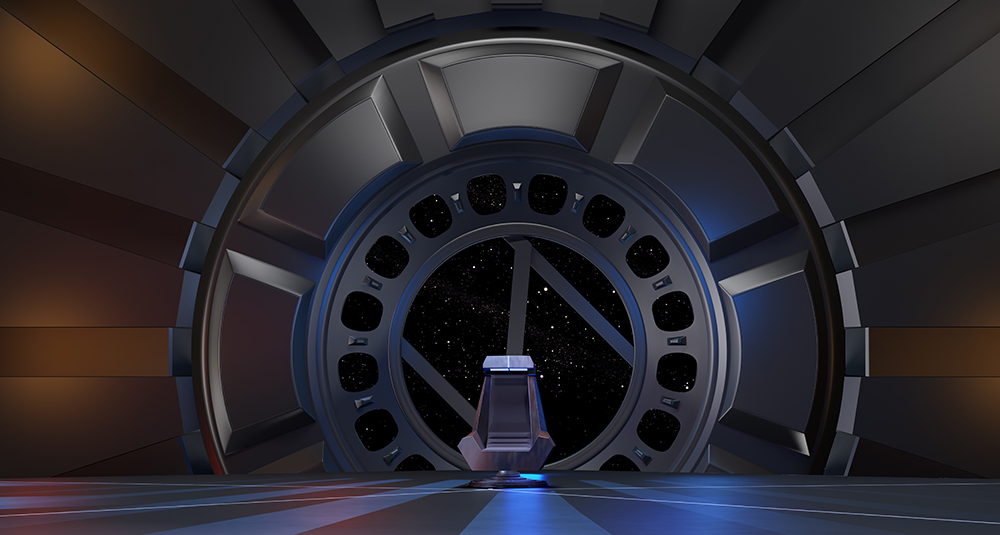

Possamai, who is now a professor of sociology at Western Sydney University, recalls watching with fascination as a new ‘religion’ exploded into the mainstream: Jediism. Inspired by the Star Wars film franchise, followers live by a doctrine centred around peace, mindfulness, positive emotions, self-improvement, and spiritual growth. They also focus on the concept of ‘The Force’ — a fictional metaphysical energy field depicted in the movies that is deemed to be the “underlying, fundamental nature of the Universe,” Possamai says.

People, he observed, were increasingly seeking inspiration for their spirituality and religion from a new source: popular culture, which includes music, television, books and films such as Star Wars and The Matrix.

“What came out of my research was that people were picking and choosing various elements of religion and philosophy together, some of which includes popular culture,” says Possamai, who first defined the ‘hyper-real religion’ concept in his 2005 book Religion and Popular Culture: A Hyper-Real Testament.

“The concept emphasises the replacement of authoritative external forms of conventional religious authority, such as imams, priests and rabbis, as well as sacred texts,” he explains.

A LIFE OF ITS OWN

The idea was revolutionary. “Possamai’s argument was quite radical because he stated that religion is not so much about a transcendent God anymore, or new age spirituality, but that people find spirituality in popular culture narratives,” says Professor Stef Aupers, a cultural sociologist at KU Leuven, a Catholic institution which is Belgium’s oldest university.

It’s been nearly two decades since hyper-real religion was conceived, and the concept has “taken on a life of its own,” says Possamai.

Today, various universities offer hyper-real religion as a key topic of learning, and other researchers have used it as a springboard for their own work — including Aupers, who previously explored how World of Warcraft players became more interested in religion and spirituality after experiencing the popular online game’s magical and paganistic elements.

Hyper-real religion has even been used to describe a range of new social practices that have emerged from texts in popular culture. These include the game of quidditch from the Harry Potter stories, chess boxing from Enki Bilal’s graphic novels, and Real-Life Superheroes — a movement in which people dress up as superheroes to patrol the streets for crime and help the homeless.

More recently, bloggers and journalists have even applied the theory to describe QAnon, the far-right American conspiracy-theory group.

“Hyper-real religion is still a very valid and interesting theory,” says Aupers. “There are all kinds of new phenomena out there.”

EVOLUTION OF AN IDEA

Over the past few decades, Possamai has further developed his concept of hyper-real religion. For instance, he’s examined how social media has hugely accelerated the spread of popular culture.

He is currently exploring the sociology of horror, which he describes as “how ideas from horror fiction and movies are coming into everyday lives through things like gothic or dark tourism, zombie walks, and hell houses.” The new research will be published in his next book, due out next year.

His focus has shifted slightly from hyper-real religion’s early days. As he explains: “My research now is to see how popular culture can inspire or influence everyday life practices outside of just religion.”

Meet the Academic | Professor Adam Possamai

Adam Possamai is Professor of Sociology and the Deputy Dean of the School of Social Sciences at Western Sydney University. His research interest is in the Sociology of Religion. He is the (co)author and (co)editor of more than twenty academic and fiction books, and more than 100 referred articles and book chapters. He is a fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences in Australia and a past President of the International Sociological Association’s Committee 22 on the Sociology of Religion. His recent sociological publications are 'Religion and Change in Australia' (with David Tittensor, Routledge, 2022), 'Sociology of Exorcism in Late Modernity' (with Giuseppe Giordan, Palgrave McMillan, 2018) and 'The I-zation of Society, Religion, and Neoliberal Post-Secularism' (Palgrave McMillan, 2018). He has recently co-edited with Bryan S. Turner and James T. Richardson the second edition of ‘The Sociology of Shari’a: Case Studies from Around the World’ (Springer 2023), with Anthony Blasi 'The Sage Encyclopedia of the Sociology of Religion' (Sage, 2020), and with Giuseppe Giordan, 'The Social Scientific Study of Exorcism in Christianity' (Springer, 2020). He is currently working on a monograph on the Sociology of Horror. He is also a fiction writer (mainly in French), and his sixth novel on the Franco-Prussian War will be published in 2025.

Credit

Future-Makers is published for Western Sydney University by Nature Research Custom Media, part of Springer Nature.

© Natalia_80/iStock/Getty

© navi_photography/Unsplash

© hermez777/Unsplash

© DFY® 디에프와이/Unsplash