You can search for courses, events, people, and anything else.

In 2018, when a student told Dr Maggie Davidson about a case of local stonemasons working with artificial stone who had been diagnosed with accelerated silicosis, alarm bells rang.

Davidson, a lecturer and researcher in occupational hygiene and environmental health at Western Sydney University, was aware of major concerns about respirable crystalline silica (RCS) and occupational lung diseases both locally and internationally, and it was immediately clear that the incurable lung disease was connected to the masons’ workplace. What horrified her was the speed with which it was progressing. “These were young men, who were dying from very rapid onset silicosis,” she said.

Having been investigating biological aerosols and biotoxins for more than 15 years, Davidson urgently wanted to understand what they were exposed to, and what could be done about it. She set about talking with workers and managers, and it was immediately apparent that they were dealing with both a complex dust mixture and multifaceted exposure to chemical (stone dust, solvents, adhesives and resins), biological (microorganisms, endotoxin), and physical (cold, heat, damp, vibration, noise) hazards.

That silicosis was being diagnosed at all was shocking to many. While known as a disease affecting construction, stonemasons, mine, and quarry workers who were exposed to RCS in the workplace, it was thought to have been largely eradicated in Australia thanks to the introduction of work health and safety regulations and more efficient controls and surveillance in the 20th century.

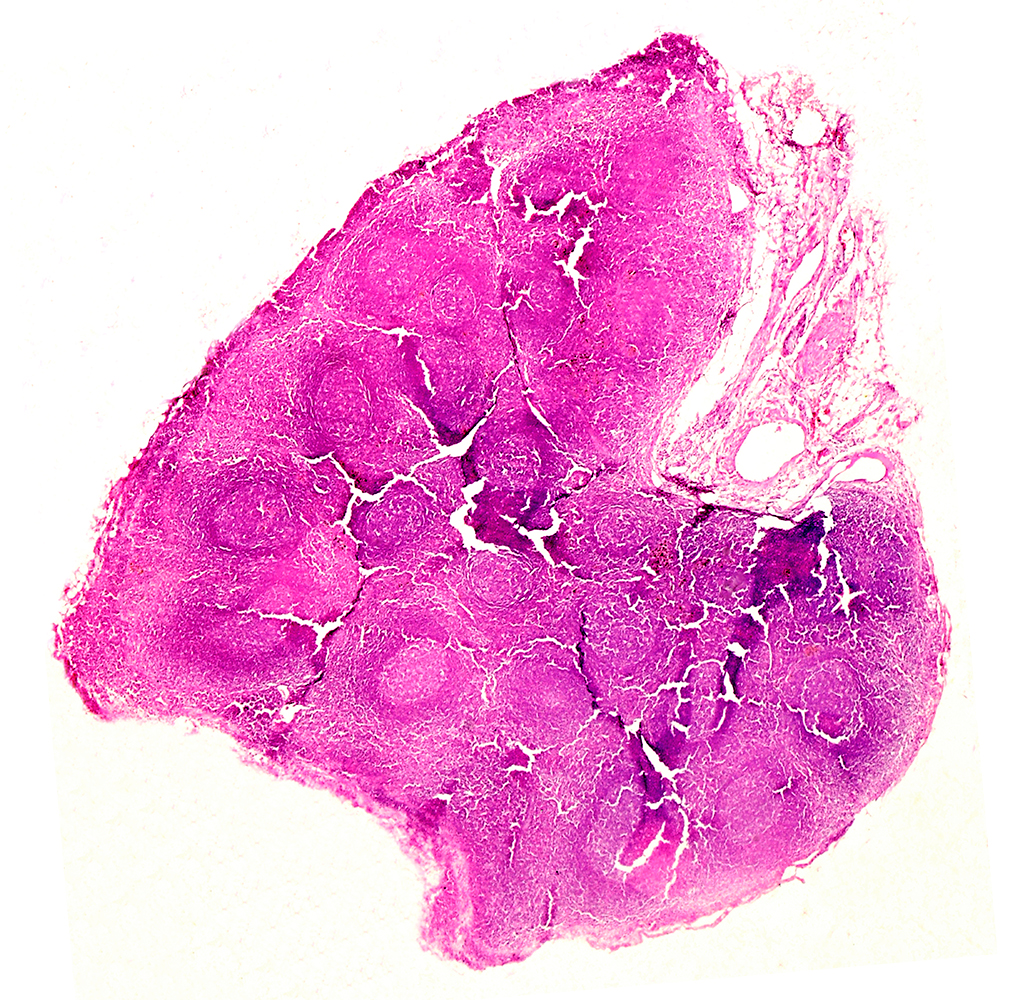

This changed with the popularity of inexpensive and accessible engineered stone — a composite material containing crushed stone, including crystalline silica, pigments and other recycled materials, bound together by a resin adhesive. Cutting it to size, grinding, and polishing for kitchen and bathroom benchtops releases fine toxic and carcinogenic RCS particles into the air which can be drawn deep into the air exchange regions of the lungs.

In 2015, a man whose job involved cutting and polishing engineered stone received a diagnosis of complicated silicosis in Australia. Soon after, stories about many silicosis-afflicted stone workers hit the news; and today hundreds of victims of what is now called artificial stone silicosis have been diagnosed. Some of the cases have been fatal.

THE BAN

Though the re-emergence of silicosis has been alarming, the response has been swift and powerful. Many respiratory physicians, occupational hygienists, and researchers, like Davidson, as well as workers, owners, unions, professional societies and government agencies, have focused attention on the crisis.

A 2020 position statement from The Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ), to which Davidson contributed, called out the failed enforcement of regulations for dust control and poor surveillance. That effort led to a 2023 report from Safe Work Australia, the Australian government’s work health and safety agency, which advised that the use of engineered stone should be prohibited. A national ban on the use, supply and manufacture of engineered stone came into place on 1 July 2024. The ban is a world first.

The ban is a victory, but it doesn’t end the story of silicosis and other occupational lung diseases in modern Australia, nor does it mean more workers won’t be diagnosed, says Davidson. Through a recent study it is estimated that more than 500,000 Australians have been exposed to RCS, and it is predicted to cause in excess of 83,000 silicosis cases, and around 10,000 lung cancer cases.

The earliest stages of the disease typically have no symptoms, so it may be years before the full toll is understood. Workers may develop shortness of breath, a cough, fatigue, and chest pain. Over time, their lung tissue will become further inflamed and scarred. They may progress to a stage where a lung transplant is required, or the condition is fatal. They are also at greater risk of developing lung cancer, tuberculosis, autoimmune disorders, and other conditions. Currently there are no effective treatments for the disease.

ALL ASPECTS OF THE DISEASE

Understanding the nature of artificial stone silicosis is critical to workers’ welfare. Davidson’s initial intuition — that there was something unusual about how fast the men were getting sick — was validated by the Safe Work Australia report, which noted that the properties of the stone appeared to be contributing towards a “more rapid and severe disease”.

When artificial stone is cut, Davidson said, the dust that is released into the air doesn’t just have silica in it, it also contains additives such as glass, resin and pigments. “It’s really complex,” she says.

To discover more about the impacts, Davidson and Western colleagues, including Associate Professor Gary Dennis, Associate Professor Sue Reed and Professor Deborah Yates, applied for a state government grant to examine the impact of these components on primary bronchial cells in a customised aerosol chamber designed to mimic real time exposure in the lungs. Whole-transcriptome RNA sequencing was used to examine cell response to the engineered and natural stone dusts.

Davidson had learnt about the technology and approach during her postdoctoral studies at Colorado State University in the United States where they were using it to identify the components in agricultural dusts that were causing lung diseases in agricultural workers. Now her team are the first researchers in Australia to use an aerosol chamber in this context to figure out the specific dust components that are most problematic, and develop targeted responses to manage exposures and reduce the risk of preventable occupational diseases.

She has now collected many samples of engineered stone dust from Australian workplaces and run numerous trials. Tissue culture supplies and data analysis were delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic, but Davidson and her colleagues have established a proof of concept: the exposed bronchial cells reacted differently to the engineered stone dust than to controls (water vapour).

The work promises to illuminate which dust constituents contribute to the rapid inflammation of the lungs, which could aid in identifying targets for treatment and generating lessons for risks to labourers working with similar products. They are also using the approach to study complex workplace dusts in other industries, and working to incorporate 3D models (organoids/spheroids) and other primary cells (alveolar, small airways, macrophage) to further refine the real-time exposure simulations and study response pathways and respiratory disease modelling.

LESSONS LEARNT

The lessons from the engineered stone industry, and the wave of silicosis, must not be wasted, say the researchers. Other instances of silicosis in the 20th century — caused by the manufacture of tatami mats in China, the sandblasting of denim in Turkey, and the creation of dental tools in the U.S. — are examples of hard-won knowledge and of the safeguards from one industry not being applied to all, says Davidson. The expanding market of recycled and composite engineered materials can help address environmental concerns. However, she adds that we must be cautious about the potential for these new products to generate toxic dusts that may harm workers during manufacture and installation, as well as in eventual demolition and recycling.

The good news, according to Davidson, is that “silicosis is now on the radar in many industries, and more funding has become available to carry out research before workers are affected.”

To that end, Davidson has also begun to investigate potential risks in the medicinal cannabis and industrial hemp industries in Australia, where internationally there has also been a re-emergence of historical allergic and respiratory diseases in workers. She is currently collecting and characterising settled and airborne dust samples from hemp mills across the country to test in the aerosol chambers and identify potential hazards.

Meet the Academic | Dr Maggie Davidson

Dr Maggie Davidson MAIOH is a Senior Lecturer in Environmental Health and Occupational Hygiene at Western Sydney University. She holds a PhD from the University of Western Sydney, with a thesis focusing on the impact of indoor smoking bans on air quality. Dr Davidson is a full member of the Australian Institute of Occupational Hygienists (AIOH) and is actively involved in various professional associations, including the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ) Occupational and Environmental Lung Diseases, Australian Institute of Occupational Hygienists and the ASTM International Standards D37 Cannabis Working Group.

Her research is currently focused on the characterising and managing respiratory health risks related to industrial hemp and cannabis dusts. Dr Davidson has co-supervised Higher Degree Research students and led industry focused research projects concerning occupational health in agricultural settings, particularly regarding bioaerosol exposure and their potential health risks for workers.

In addition to her teaching and research, Dr Davidson has contributed to the development of OHS standards alongside colleagues in AIOH, TSANZ and ASTM. She was lead author for the Biological Hazards Chapter in the 2nd, 3rd & 4th editions of the AIOH Principles of Occupational Health and Hygiene and has been awarded for her research impact working for the prevention of occupational lung diseases (engineered stone and silicosis). Dr Davidson continues to advocate for improved health and safety practices in both the agricultural and industrial sectors and is committed to enhancing workplace environments and worker wellbeing.

Credit

Future-Makers is published for Western Sydney University by Nature Research Custom Media, part of Springer Nature.

© Nigel Downer/Science Photo Library

© unkhz/Unsplash

© vwalakte/Freepik