Is Feminism Dead? A Conversation With Professor Deborah Stevenson

Professor Deborah Stevenson is a sociologist for whom feminism and gender are important areas of research focus. We chat to her about resistance among many young women to identifying as "feminist", and the potential role of online spaces in reviving young Australian women's interest in this movement.

You've demonstrated a commitment to exploring feminist tenets and gender issues in much of your research—whether it be in investigations of cities and urban life, globalisation or the politics of generational change. Why is feminism and gender a recurring theme in your research?

If gender is something of a recurring theme in my work then this is because, along with class, ethnicity, and age, it is a key social fault line – a source of structural inequality as well as of identity and empowerment. So no matter what the social phenomenon being examined is, there will be important gender dimensions that should also be revealed and probed. Some of my work has been explicitly concerned with gender and I'm thinking here particularly about the ARC Project which took a generational approach to understanding the socio-cultural factors influencing the attitudes of Australian women towards work, ageing and retirement. This project was keen also to explore what feminism meant to women of different ages and to understand in what ways it has influenced their lives. In other work I've done gender is a theme but not necessarily the central focus. For instance, my work on cities and urban cultures has highlighted the different ways in which women and men use and engage with the city. I am, however, always keen to avoid generalising from the experiences of one group/cohort of women to all women. Research into the night-time economy is a case in point here. While there is strong evidence that women use the city at night in quite different ways from men, it is also the case that there are very clear differences between the ways in which women use it, with age being a key variable.

Some researchers have argued that there is no such thing as 'feminist research', rather, research with a deep feminist consciousness is simply 'good' research. Do you consider your research "feminist"? Why, why not?

My research is not 'feminist' in any intrinsic sense but I do regard myself as a feminist and so this obviously influences my research concerns. I struggle with the idea that there is a form of, or approach to, research that is inherently feminist because good social research is by definition engaged, nuanced and open. Being a feminist and having feminist concerns does not lead automatically to the production of good research or sharp insights. In fact, it can cut off ways of seeing and interesting lines of enquiry. The most incisive feminist research is often qualitative and perhaps even ethnographic, but there is also a place for quantitative research and for exploring themes and issues across populations. The generational study of women, work and retirement that I referred to above utilised both qualitative and quantitative methods and was the richer for it. As with all social research the starting point should be the research question – what is it you want to know? – and the methodology follows.

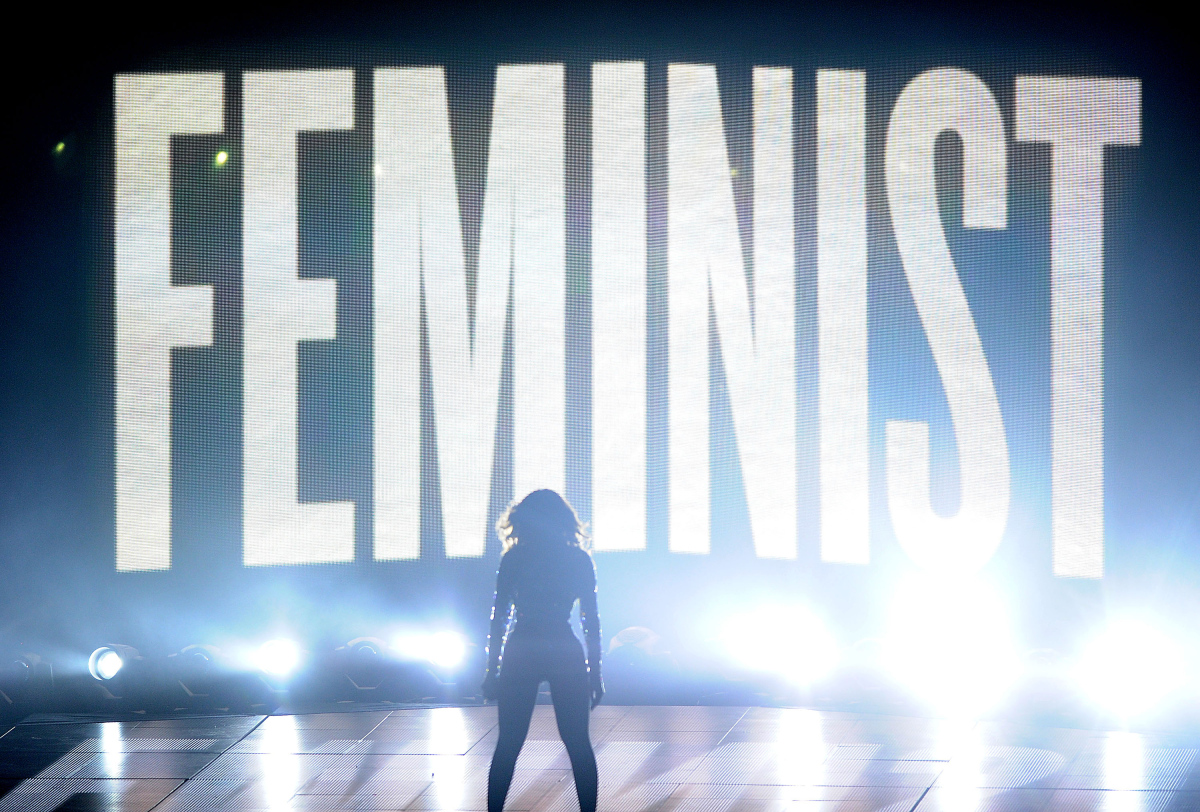

Jason LaVeris – FilmMagic/Getty Images

Research from your ARC project 'Women consider retirement: a critical investigation of attitudes towards work, ageing and retirement in three generations of Australian women' which identified socio-cultural shifts in attitudes in three generations of Australian women, concluded, among other things, that young Australian women are less likely to identify as "feminists" than older generations of Australian women. How important do you think identity politics are to the feminist project?

Identity politics has become an important aspect of contemporary feminism although whether it's advancing the feminist project is a moot point.The second wave feminist project was focused on universal principles and achieving overarching objectives such as equal pay. In other words, it was concerned with social institutions and practices. It was a social movement underpinned by social theories and ideologies and informed by shared experiences and explanations of this experience. In recent years, these objectives, foci and the resulting gender prescriptions have been roundly challenged by younger feminists, particularly those concerned with identity. The view that being a feminist somehow means being a man-hater, asexual and frumpy has become common and young women are less likely to identify with collective feminist politics than older women. Their feminism is one focused on the individual and, as you say, identity, and it is this focus - along with the associated retreat from a collective political project - that concerns older (second wave) feminists.It is also the basis of the argument that younger feminists have abandoned the feminist project. The counter argument is that the feminist project has changed and its politics is played out in different spaces (including the virtual).

But, of course, the lives of women are shaped by many factors including class, ethnicity, race, location, generation and the like, as well as by culture. The challenge for contemporary feminism is to find a theoretical and political language for dealing with this complexity/multiplicity and not slip into binary oppositions or generationalism. It isn't that young women see the broad objectives of second wave feminism as unimportant, but that women no longer feel collectively constrained by the fact that they are women. A key shift has been in what it means to be a woman and in how constraints experienced at the level of the individual are understood. The argument that my co-authors and I put forward in our article 'Choices and Life Chances: Feminism and the Politics of Generational Change' (opens in a new window) is that, compared to second wave feminists, young women are less likely to experience/interpret constraints on their choices in terms of their gender.

(L): by Larry Oien and (R): by Gaelx

You contended in 2011 in your co-authored article 'Choices and Life Chances: Feminism and the Politics of Generational Change' that although younger generations of Australian women still face the pressures and constraints of gender, for example with motherhood continuing to shape their working arrangements, they do not tend to use gender equity discourses to make sense of these pressures, and largely, take gender equity for granted.

Interestingly, the years following your publication have been important for contemporary feminism, with Anne Summers arguing that 2012 was the "best year for Australian women since 1972". That year also saw Australia's first female Prime Minister denounce sexism and misogyny in federal parliament (which attracted global attention); the inception of online publications such as Women's Agenda and Daily Life, which provide diverse voices and perspectives on being a woman in Australia; and much online feminist activism by young women like the national trending of #destroythejoint and #everydaysexism. This 'revival' (as some social commentators are calling it) of feminism has no doubt seen gender equity discourses re-enter public discussions and discourse.

The 'connectedness' of online spaces has enabled young Australian women to foster activist-related relationships, to share their stories, which, in turn, has facilitated a collective concern with women's liberation. Do you think that online spaces can revive young Australian women's interest in feminism?

Online spaces are important to contemporary feminism. There are numerous websites and online publications such as those you mention that are playing important roles in providing women with spaces for their activism. The problem though – and this is a general problem with blogs and other online fora, special interest or otherwise – is that often these sites speak to and engage the already converted. People seek out sites that interest them. They serve a purpose – often an important one – in providing a point of focus and shared expression. But it's hard to see these spaces being prompts for collective action as opposed to collective discussion. I wonder, though, whether it's accurate to describe the sites as being pivotal to reviving Australian women's interest in feminism. I tend to see them as critical elements of a reshaped or a reshaping of feminism. It is also important to remember that, at the same time as we've seen the development of these online spaces and a general increase in discussions about the place of women in society, we have also witnessed the use of online spaces for the expression of misogynistic views. Julia Gillard's now-famous 'misogynist speech' has been described by many as being prompted at least in part by the hatred of her as a woman expressed on websites and social media. So, as is the case more generally, it is important not to overstate the importance and effect of social media.

Image at top: Pussy Riot Global Day by Eyes On Rights

15 October, 2014