Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital: 1888 to 1980s

Why was the Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital established?

Facilities like Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital were established with the intention of not just accommodating, but segregating people who had some form of mental illness, out of concern for the character of the population as a whole. Many psychiatrists practicing at the time of the establishment of the Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital believed in the theory of eugenics, and saw the isolation of the mentally ill in such facilities as an important way of ensuring that ‘mental defectiveness’ was not passed on to subsequent generations.

Click on images above

The original Female Orphan School building underwent extensions and renovations in order to house the patients of the hospital – the east and west wings were further extended to provide accommodation, and the verandas of the building were enclosed. Particular emphasis was placed on the natural environment around the building in the belief that this would assist in the recovery of patients. The land around the building was landscaped extensively – in 1893 the Royal Botanic Gardens sent 275 trees and 120 shrubs to improve the gardens on the site.

Who came to the Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital?

The hospital received many different kinds of patients over its century-long history. Patients were admitted for reasons that today seem strange. This is because of changing understandings of mental illness, and evolving approaches to its management. At the time ‘lunatics’ were first admitted to Rydalmere Hospital for the Insane, understandings of the nature of mental illness, and what should be identified as mental illness were very different from those held today. Moreover, there were few effective treatments available to manage it, and therapies were rudimentary.

The 1878 Lunacy Act which governed the operation of facilities like Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital defined insanity very broadly. An ‘insane person’ was deemed to be “any person who shall for the time being be idiotic, lunatic or of unsound mind and incapable of managing himself or his affairs and whether found insane by inquisition or otherwise”.

One of the dominant understandings of 'insanity' defined both ‘moral’ or ‘physical’ causes of the condition. The 1900 Statistical Register of New South Wales defined the following conditions as either ‘moral’ or ‘physical’ causes of insanity.

| Moral Causes | Physical Causes |

|

|

In the 1880s, most patients were admitted to facilities like Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital by court order, and in many cases this was the result of an arrest by the police. Other patients were referred from general hospitals or charitable organisations, or admitted at the request of family members who felt unable to care for them and in some cases, felt threatened by them.

Sometimes, patients admitted themselves, presenting to a police station or the Reception House for the mentally ill in Darlinghurst to have themselves certified as insane. In the 1880s, most requested admissions to insane asylums came from women, despite the fact that there were more men admitted to the asylums overall by a factor of three to one. This may have been because notwithstanding a man's mental state, his family may have been reluctant to commit a male breadwinner to an asylum and thus forgo the income necessary to support the family.

Click on the documents above

In the 1880s, single men and women were overrepresented in the populations of Sydney’s mental hospitals, as were patients from low-skilled jobs and working class backgrounds. A quarter of male patients had previously worked in skilled jobs, and a tenth were middle class – having previously worked as bankers, merchants, accountants, clerks and shopkeepers. A smaller group still consisted of clergymen, doctors, lawyers, engineers, graziers and squatters.

Initially the hospital only accommodated male patients, however female patients were later. Female patients were housed separately on the site from 1895, away from the Orphan School building, which only ever accommodated male patients. Most of the early patients had dementia or suffered from other chronic conditions with minimal chance of recovery. However, once the facility became independent of Parramatta Hospital for the Insane, patients with a wider range of conditions were admitted. Patients with schizophrenia were taken there, including the poet Francis Charles Webb. Although patients with epilepsy and the ‘mental defectiveness’ were admitted, the proportion of older patients remained substantial and indeed grew over time. By 1947, the hospital accommodated 300 epileptic patients, and 300 patients with senility, and together these groups constituted about half of the overall hospital population. Geriatric and dementia patients continued to constitute a large part of the hospital population until the end of its existence. In 1970, the average patient age at Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital was 76. Because most of the illnesses suffered by patients at Rydalmere were deemed to be chronic, they were often regarded as ‘hopeless’ by the staff.

Whilst the accommodation of patients with epilepsy in a psychiatric facility would today be seen as inappropriate, objections were raised to their detention there even as early as 1923, during Royal Commission hearings on the state of New South Wales’ mental health facilities. One doctor, highlighting the inadequacy of the government’s approach to mental health cited the case of a saleswoman working in a city department store who had an epileptic seizure in front of staff and customers. She was sent home sick, and returned to work without incident for six months before suffering another seizure. This time she lost her job and was taken by her family to a mental health facility, where she was then certified and sent to a mental hospital, and accommodated with people with a wide range of mental health issues.

What was life like in the Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital for patients?

It is difficult to describe what different patients’ experience of the hospital was like. There are a number of reasons for this. Because each patient’s experience of the place was shaped by their own personal history and condition, there was no ‘universal’ patient experience of Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital. Furthermore, there is little documentary evidence left by patients for us to interpret, and photography in psychiatric institutions such as Rydalmere was prohibited. By law, medical records of the patients accommodated at Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital are sealed for 110 years. More will be known about the experience of patients at the hospital place once these medical records can be accessed by historians.

However, some information can be gleaned from accounts recorded by staff. Even in the 1920s, doctors were concerned by the poor conditions at the hospital. Dr Edwards described his experience of starting at Rydalmere in this way:

“Rydalmere was an introduction to the ‘lunatic asylum’ at its worst…With one exception – the female convalescent ward – the wards were dingy and antiquated…the wards were even more repelling and soul-killing inside. Most of the rooms were painted a dull green or a peculiar unattractive shade of brown. Nearly all floors were washed every morning and the damp bare boards for hours afterwards added to the asylum smell of urine, faeces and unwashed bodies.”

For most of its history, the patients of the Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital were given standard uniforms. Men were given shapeless clothes made of coarse grey tweed, a cloth hat, and heavy boots. Women were given a shapeless dress made of strong blue or grey fabric. Dr Edwards noted that this was a source of ‘constant shame and hostility amongst the women’.

Click on the image above

One of the defining characteristics of life at Rydalmere was overcrowding. For most of its history, the number of patients at the Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital was around 1,000. This had a number of effects. The overcrowding problem accelerated the spread of communicable diseases. The confinement of patients suffering widely varying conditions was recognised by the management of the institution as a problem even early in its history. The overcrowding problem became self-perpetuating. As more patients were admitted beyond Rydalmere’s capacity to house them, the standard of treatment declined – and the proportion of long-term patients increased, as did the rate of re-admission for previously discharged patients.

Some former patients have noted inappropriate accommodation practices – such as children and adults being accommodated in the same quarters, and others have reported that they suffered from assault by other patients. Indeed, there are numerous newspaper reports of assaults and several reports of murders taking place at the hospital.

Dr T. A. Edwards, who worked at Rydalmere in the 1920s, concluded that the asylum system itself was actually exacerbating mental illness. For example, accommodating patients designated as ‘violent’ together provoked violent incidents rather than prevented them. The strict confinement and isolation from visitors and activities was also a contributing factor. There are records indicating that a number of patients at facilities like Rydalmere complained about the injustice of their being incarcerated, however these complaints were often simply noted by doctors as further evidence of their delusion and insanity.

Meals at state mental hospitals like Rydalmere were often repetitive. A typical daily meal in the 1920s would have consisted of bread, butter or perhaps porridge, with tea of coffee. Dinner usually consisted of meat such as beef, mince meat or mutton with potatoes but few other vegetables. The hospital generated its own supply of fresh food by keeping gardens and livestock.

The age of the former Female Orphan School buildings had an impact on the quality of life for its patients. Even in the late 1960s, the building had no hot running water, and each morning nurses had to carry buckets of hot water to shave the men who were accommodated there.

From the time of the foundation of the hospital, its staff offered a range of recreational activities to patients in the form of trips to the Roxy Theatre in Parramatta, fancy dress parties, dances, concerts, musical performances, fetes and sports matches. Boats were also provided for the use of some patients on the Parramatta River. Until at least the 1930s, patients were required to be in bed by 5:30 pm.

What treatments were given to patients?

Treatment of mental illness changed dramatically over the life of the hospital. Inspector General of the Insane, Frederic Norton Manning, who was responsible for the operation of Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital at the time of its establishment identified five major causes of insanity – isolation, anxiety, intemperance, sunstroke, and hereditary factors. On this basis, Manning and his doctors practiced a number of therapies. Manning was committed to the ‘moral therapy’ approach to mental illness, which promoted the provision of work, religious instruction and pleasant surroundings for patients.

For much of its history, the main treatment approach, according to historian Stephen Garton, was to provide ‘work, rest, food and sympathy’. Men were encouraged to engage in manual labour in the hospital grounds, and women were encouraged to practice domestic work – helping in the laundry and sewing room. Whilst this work wasn’t compulsory, patients’ willingness to participate was interpreted as an indicator of their progress and potential for discharge. As an encouragement, extra rations were given to patients who undertook work.

During the second half of the 19th century, the range of pharmaceutical treatments was very limited – alcoholic dementia was treated with arsenic, strychnine and ammonia, and opium was used to calm patients. Potassium bromide and chloral hydrate were used in facilities like Rydalmere for a long time. It has been suggested that the use of these drugs was more for the benefit of staff rather than patients because it served to calm patients’ behaviour and make it easier for the understaffed hospital to control the large population of patients.

Click on the document above

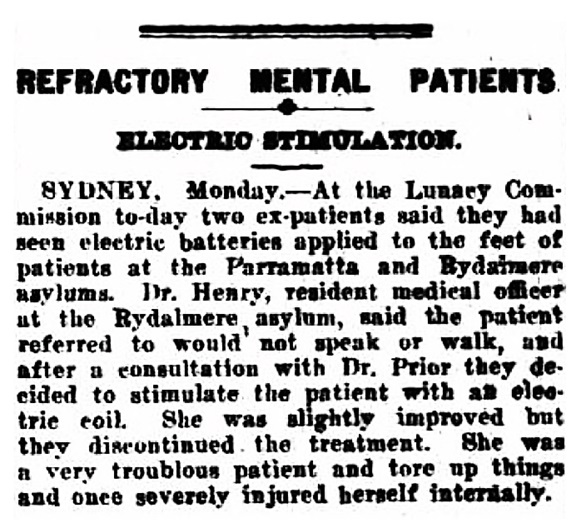

Electrotherapy, which involved applying an electric current to different parts of the body, was also employed, as well as a range of experimental treatments. The extent to which patients consented to these treatments is unclear, but the treating physicians had significant authority over patients’ treatment regimes. Psychiatrists were authorised to administer any ‘essential treatment’ to a certified patient, regardless of whether that patient had given their consent.

As greater resources were diverted to patients thought to be curable, conditions for chronic patients such as those at Rydalmere declined, and according to Stephen Garton, there was a 20% increase in the use of patient restraint between 1900 and 1940 in New South Wales’ psychiatric hospitals.

What happened to patients at Rydalmere?

The outcomes of the hospital’s patients varied over time, as understanding of mental illness changed, and treatments for it developed. In 1908, the Inspector General of the Insane reported that 42% of patients admitted to its care that year had recovered and were discharged.

Generally, the longer a patient stayed in the facility, the less likely it would be that they would ever be discharged. Most of the patients that were discharged as ‘recovered’ were released after less than a year. Patients who had not recovered but were deemed ‘harmless’ and non-violent could be discharged to the care of their family.

Click on the image above

Some patients in Sydney’s mental asylums were allowed out of the institution on ‘leave’ and given significant freedom of movement. Many of these were discharged as recovered while they were on leave. This would have been the case for some patients at Rydalmere.

Other patients recovered from their initial condition but became so accustomed to life within the hospital, and so dependent on the services that it provided that they were unwilling or unable to leave. These patients were known as ‘asylum-sane’.

A significant number of patients died in facilities like Rydalmere. In the 1880s, 13% to 18% died of old age, 10% died of epilepsy and tuberculosis, and between 10% and 17% died of an unexplained disease described as ‘maniacal exhaustion’.

Occasionally, newspapers reported on the escape of patients from the hospital, although government records indicate that the vast majority of attempted escapes were ultimately unsuccessful. Curiously, under the New South Wales Lunacy Act any escaped patient who was not recaptured within 28 days was deemed recovered and discharged.

What was life like in the Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital for staff?

Just as there was no universal experience of patients at Rydalmere, there was no universal experience of staff. Some were better suited to the demanding work there than others, and whilst there were certainly instances of misconduct by hospital staff, there were also a great many that discharged their duties admirably, under difficult circumstances. At some stages in its history, it was required that members of staff live onsite at the hospital.

Click on the image above

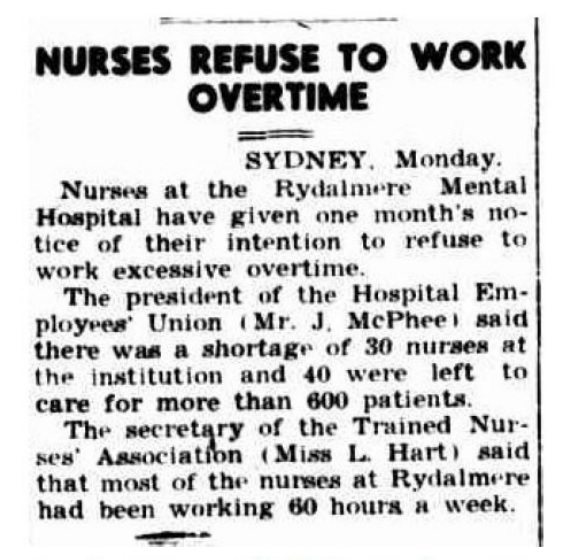

The work performed by the staff of the Psychiatric Hospital was demanding. The overcrowding and underfunding the facility perpetually suffered exacerbated this. For much of its history, the range of medications that could be prescribed to patients and incomplete knowledge about the nature of mental illness limited the therapeutic options available. The high rate of staff turnover over the institution’s history reflects the difficult nature of the work, and the challenging conditions. In 1945 for example, the nurse’s union complained that most nurses at Rydalmere worked 12-hour days, and got only one day off in six, rather than the one day off in every three to which they were entitled. The union complained about the severe understaffing at Rydalmere, which led to 44 nurses doing the work of 70. The union argued that this led to many staff becoming ‘ill from overwork’. In August 1945, the staff at Rydalmere enacted a ban on working excessive overtime. The understaffing of the hospital may have compromised the safety of staff there, who were occasionally subject to attacks by patients.

At the 1923 Royal Commission on Lunacy Administration, medical staff praised the treatment of patients by nurses and attendants. One doctor claiming that in nine years at Rydalmere, he had never seen a patient punished or ill-treated, and that nurses had treated patients with tact and kindness. Evidence from former patients differed from this. Several claimed that patients had been ‘tortured’ as punishment. One claimed that a doctor and nurses had applied electric batteries to the feet and ears of one patient as a punishment. The behaviour of some staff towards violent patients by staff was sometimes criticised. One doctor working at the hospital in the 1920s recalled that “a small proportion of the attendants and nurses got sadistic pleasure out of provoking them”.

-- Who was Dr Sylvester Minogue? --

Despite this, evidence such as internal staff newsletters indicate that the hospital staff included a great many who were genuinely committed to the care and well-being of patients, and the improvement of treatment programs for them. One doctor working at Rydalmere noted that the work of ‘mental nurses’ was not properly respected or appreciated, and that those who expressed derision for these workers “had little idea with what devotion many of them looked after their charges”.

Why did the Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital close?

As early as the 1940s, serious concerns were raised about the treatment of mentally ill patients in large institutional facilities throughout New South Wales. In 1949, the Sunday Herald pointed out that at Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital, there were only three doctors employed to care for over 900 patients, describing the system as ‘unscientific, obsolete and inhuman’, treating patients like ‘convicts and animals’. It was argued that the accommodating patients in buildings that weren’t designed for that purpose (such as the Female Orphan School building) meant that patients were treated more like prisoners – an experience that exacerbated their conditions rather than eased them. It was said that the overcrowding, and lack of individual care meant that mental illness was treated simplistically, without an appreciation of the fact that mental illness came in many forms, and was caused by many different factors. Patients with developmental disabilities, epilepsy, mental illness and dementia were treated with a lack of differentiation that was greatly at odds with newer understandings of these conditions.

The management of patients accommodated in facilities like Rydalmere gradually changed over the second half of the 20th Century. By the 1960s, the treatment of psychiatric patients with new medications meant that their detention in custodial environments like the Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital was seen as unnecessary.

The New South Wales Government eventually responded to concerns about the mental health care system by commissioning the Richmond Report in 1982. This report recommended the closure of large mental asylums in preference to small group homes as well as the provision of more specialised services and community care. By 1986, fewer than 300 patients remained at the hospital, and it closed in stages over the years that followed.

The Female Orphan School building itself had been closed in 1969, as it had become increasingly dilapidated and the patients accommodated there were moved to newer facilities elsewhere on the Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital site. The Female Orphan School building was occasionally used as an indoor basketball court for patients throughout the early 1970s, but it was surrounded with wire fencing in 1975 to prevent illegal entry.

Related Documents

- Website text with footnotes (PDF, 382.37 KB) (opens in a new window)

Mobile options: